By Stephen Schmidt

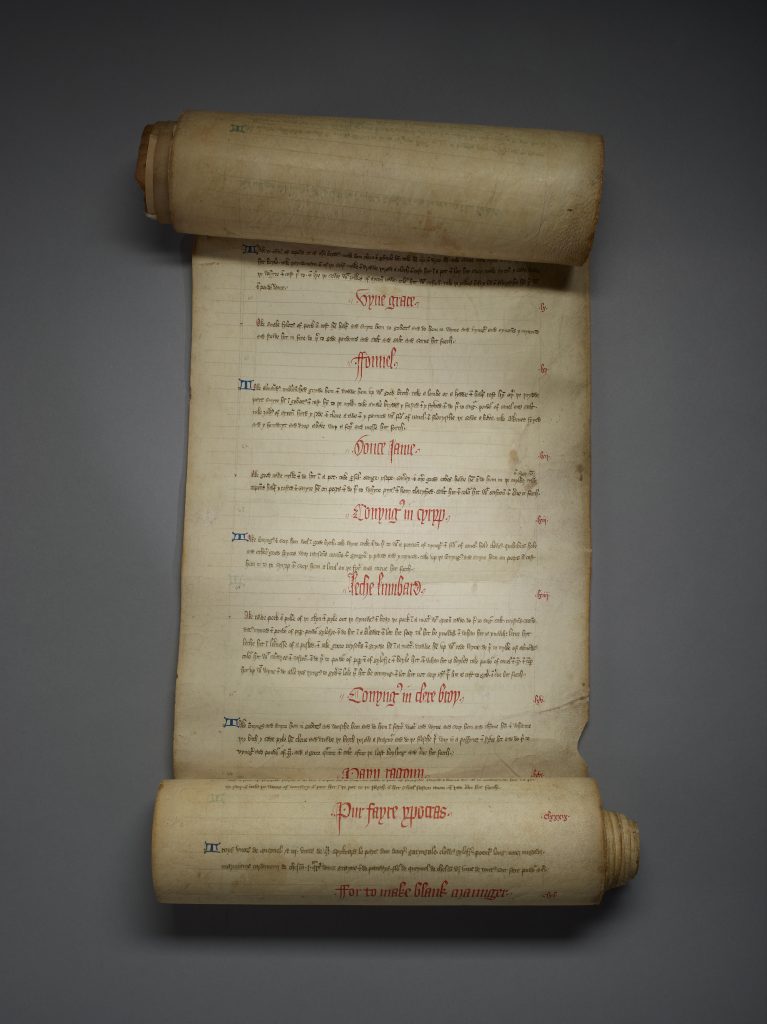

MS Buhler 36, 15th century English cookbook, Morgan Library

Recently, the Manuscript Cookbooks Survey hosted a medieval English dinner for a committee of medieval and Renaissance manuscript scholars associated with the Morgan Library and Museum, in New York City. I was the cook. People often ask how any cook today can presume to reproduce medieval food as it was made in its time since most medieval recipes omit quantities of ingredients and provide only sketchy instructions with regard to procedure. The honest answer, of course, is that no cook can. A cook can only “interpret” medieval recipes using his or her intuitions. Mine are informed by reading I have done over the past few years about medieval Islamic culture, including its cuisine, and its impact on Europe. The extent of eastern influence on the cuisines of the medieval Christian West is controversial among medieval scholars. In Out of the East: Spices and the Medieval Imagination (Yale University Press, 2008), Paul Freedman footnotes two authorities, one who sees extensive eastern influence and one who proclaims that “medieval [European] taste is not Arab.” I am not a medieval scholar. But, speaking as a cook, I taste the East and sense its technique in western medieval European cooking. And as a casual reader of medieval history, I see much circumstantial evidence that corroborates my culinary intuitions.

When a late fourteenth-century English manuscript cookbook known as Forme of Cury was first printed, in 1780, the myriad spices and the sugar with which its dishes are seasoned incited bafflement and revulsion in many readers—a reaction still echoed today in the seemingly unkillable myth that medieval spices served to camouflage the taste of rotten meat, as though the princes and wealthy merchants who, alone, were privileged to taste medieval haute cuisine had only rotten meat at their disposal. Still, we can hope that the myth, at long last, may be slain. As a guest at our dinner astutely commented, we have a greater openness to medieval European cuisines than did Americans in the past, for we are familiar with the headily spiced, subtly sweet cuisines of Thailand, India, Persia, Morocco, and Mexico—and we very much like them. I was delighted by this guest’s comment, for I felt she had intuited my interpretation of the dishes of our dinner. The cooking of the medieval Islamic world still survives today, to varying degrees, in most cultures that medieval Islam touched, and the contemporary cooking of these cultures informs my interpretation of medieval European recipes.

1.

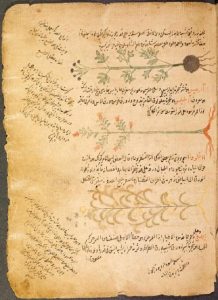

Al-Wasiti, 13th century Baghdad library Muslim Heritage

The Golden Age of medieval Islam was forged during the ninth and tenth centuries in Baghdad, seat of the third Islamic caliphate. Baghdad’s many achievements in philosophy, science, medicine, painting, poetry, and music are largely attributable to its openness to diverse sources of knowledge, symbolized by the famed House of Wisdom, a network of academies that translated all of the world’s known learned manuscripts—Indian, Persian, Syrian, Egyptian, and Greek—into Arabic. The ancient, sophisticated culture of Persia, conveyed both through translated Persian texts and by the many Persians living in Baghdad, exerted particular influence on Golden Age Baghdadi culture, including Baghdad’s lush, fragrant, complex cuisine. High cuisine could flourish in Golden Age Baghdad because Baghdadi culture embraced pleasure. An early fourteenth-century Baghdadi cookbook, translated by Charles Perry as A Baghdad Cookery Book (Prospect Books, 2005), begins thus: “The pleasures of this world are six: food, drink, clothing, sex, scent, and sound. The most eminent and perfect of these is food, for food is the foundation of the body and the material of life.” Baghdad was sacked by the Mongols soon after these lines were written and all of its manuscripts thrown into the Tigris, so that the river was said to have run black with ink. But by this time, the culture of Baghdad, including its glorious cuisine, had been transmitted across the Islamic-ruled world, which stretched from India, across the entire Middle East and North Africa, and into Iberia. The Christian West tasted dialects of this cuisine when it came into contact with two Islamic cultures located within Europe itself, those of Spain and Sicily.

Cathedral of Toledo, principal site of Latin translations, Wikipedia

During what might be called the long twelfth century, Christian Europe, long an isolated, ignorant backwater of squabbling fiefdoms, was experiencing an economic and political awakening along the Mediterranean, where long-dormant trading networks were being reestablished, leading to knowledge exchanges and the emergence of vibrant cultures in northwestern Spain, Provence, and the Italian maritime city states. During this time, much of Islamic Spain and all of Islamic Sicily came to be ruled by Christian forces. The new Christian rulers of Spain and Sicily recognized that these advanced Islamic cultures provided useful paradigms for Christendom going forward and, for a time, protected and preserved them. Spain’s particular glories were its libraries, which held thousands of Arabic-language learned manuscripts, some original to the Islamic world, by its Muslim, Jewish, and Christian thinkers, and some penned by the great Greek savants of antiquity, which the Islamic world had preserved, in Arabic translations, but which the West had mostly lost. Modeled after the original Baghdad House of Wisdom, a series of projects to translate these manuscripts into Latin were undertaken under Christian auspices, first in Toledo and later in other Spanish cities, prompting scholars, prelates, poets, artists, and other would-be translators from throughout Christian Europe to descend on Spain in droves. Sicily, too, had manuscripts, and many came to Sicily to translate them. But more came simply to bask in Sicily’s luminous culture, particularly that of Palermo, the capital city, with its religiously diverse, polyglot population, its gorgeous mosques, churches, and palaces, and its artists, musicians, and poets.

Lusterware bowl, Persia, 9th to 11th century

Sadly, the lesson of social and religious tolerance that the West might have learned, particularly from Norman Sicily, was the one it most flagrantly ignored: the first of the murderous Crusades was inaugurated in 1095, and after 1250, Christian-ruled Spain and Sicily, too, descended into intolerance and persecution. (To be fair, much of the Islamic world had lost its tolerant luster by this time.) Still, the benefits of Islamic contact to Christendom were immense. The long twelfth century saw a flowering of western Christian culture now known as the Twelfth Century Renaissance, which launched the iconic achievements of the European High Middle Ages: the opening of the West’s first universities and medical schools; the building of the first Gothic cathedrals; Giotto’s stunning frescoes and altarpieces; and the rise of the Arthurian legend and other medieval narrative cycles that beguile us today with their themes of knightly chivalry and courtly love. Other than the universities and medical schools, which were indisputably spurred by the translations, it is unclear to what extent contact with Spain and Sicily fueled the Twelfth Century Renaissance. But that Christian Europeans were deeply impressed by Spain and Sicily and sought to assimilate their cultures is proved by the massive trade in eastern luxury goods that soon ensued, including silk brocade and other eastern textiles, intricately patterned carpets, iridescent lusterware ceramics, vividly painted tin-glazed pottery, clear glass mirrors, and paper (which was ever so much lighter than vellum, the only book material that Christian Europe knew). Eastern fabrics and carpets can be seen in many Renaissance paintings, as can a decorative (but meaningless) script that resembles Arabic, which Europeans believed was the language Jesus spoke.

In addition to ogling the luxury goods of twelfth-century Spain and Sicily, the Christian travelers tasted their cuisines. In the case of Spain we have some idea what this cuisine was like, for it is recorded in an exhaustive Arabic-language cookbook that was compiled around 1400 from earlier recipe manuscripts penned during the rule of Spain by the Moroccan Almohad dynasty, which roughly spanned 1150 to 1230. Translated into English, principally by Charles Perry, as The Anonymous Andalusian Cookbook, this book outlines a lush, sophisticated cuisine broadly similar to that of the Baghdadi cookbook but also incorporating dishes that originated in Morocco, Spain, and elsewhere. Unfortunately, there is no surviving manuscript record of twelfth-century elite Sicilian cuisine, but we know that it was Islamic-inflected, for a visiting Spanish Muslim scholar wrote, in 1184, that Palermo still retained a Muslim character and that the Norman king, William II, continued to rely on Muslims “to handle many of his affairs, including the most important ones, to the point that the Great Intendant for cooking is a Muslim.” Given the beauty of period Sicilian culture, we can assume that this cuisine was as sophisticated as that of Spain, if also different, as Sicily had a unique population and history.

Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II (r. 1230-1250), whose Palermo court was said to be “Saracen”

One apparent consequence of Christendom’s culinary contact with Islamic Spain and Sicily was a new interest in, and respect for, cooking in the West. Other than a few recipe fragments, there is no surviving written record of what was cooked anywhere in Christendom prior to contact with Spain and Sicily. After contact, dozens of recipe manuscripts were written, first, around 1200, in the northern reaches of the Holy Roman Empire (perhaps inspired by the cooking of the empire’s court, which was located in Sicily between 1194 and 1250 and was widely alleged to be “Saracen”), and later in England, France, Italy, and Spain.1 While the cuisines outlined in these manuscripts are unique, they share enough similarities to be characterized as variants on a common haute cuisine of the late-medieval European privileged. This cuisine is by no means eastern. Relatively few eastern dishes turn up in medieval European recipe manuscripts.2 But an influential “foreign” cuisine does not make its impact primarily via recipes it leaves behind but by overlaying a native cuisine with new tastes, new ingredients, and new techniques. Christian Europeans appropriated those elements of Spanish and Sicilian cuisines that, for whatever reason, exerted particular appeal, and used them to transform their native cookeries.

It is clear that one of these elements was the seasoning of foods with spices, sometimes in combination with sugar, a pervasive feature of medieval eastern cuisines and likewise pervasive in all manner of late-medieval European dishes, from meats, to fish, to vegetables, to pastas. Except for pepper, ginger, galingale, cumin, and fennel, all of the spices used in medieval English cooking first enter the written English record after the twelfth century, including both spices imported from the East (cinnamon, cloves, nutmeg, mace, cardamom, cubebs, and grains of paradise), and those cultivable in England (saffron, mustard, anise, caraway, and coriander). Sugar was indisputably a gift of the Islamic world. Most of Europe had never heard of it until the opening of Toledo and Palermo in the late eleventh century.

Mortar & pestle with Arabic or Kufic script

Another transformative culinary element borrowed by the West from the East was almond milk, a critical ingredient in many medieval European sauces, stews, porridges, and still other dishes. Also inspired by the East, I believe, was the medieval European obsession with pounding foods to pastes in a mortar, the linchpin of innumerable sauces, porridges, pastry fillings, and forcemeats in the Andalusian cookbook, in which the word “pound” occurs 371 times. The mortar and pestle are ancient, nearly universal tools, and medieval European cooks surely pounded some foods long before contact with Spain and Sicily, as had the Romans before them. But I think it unlikely that early Christendom pounded on anything like the scale indicated in the later medieval recipe manuscripts, for pounding is time-consuming and laborious, and I doubt that early Christendom was sufficiently engaged in cooking to bother. Whatever the purely gustatory merits of pounding, there was likely a broader reason that the technique became so central to medieval European cuisines. As Paul Freedman suggests in Out of the East, pounding was indispensable to a primal project of medieval cooks, which was to disguise or transform foods and thereby invoke sense of mystery and wonder. Mysterious spicy sauces with pounded bases, reminiscent of “curries” and Mexican moles, were the most characteristic conceit of this project. But there were many others, including hash-like concoctions known as “mortar dishes,” meatballs coated in saffron-tinted batter and presented as “golden apples,” and forcemeat tarts suggestive of birds’ nests, with whole songbirds poking out.

Ibrâhîm ibn Abî Sa’îd al-Maghribî al-‘Alâ’î, 12th century book of simples Muslim Heritage

The eastern borrowings by the medieval West swell still more if recipes for confectionary and sugar preserving are included. In the medieval Islamic world sugar was not only a food but also the most potent and most used drug in the Islamic formulary. Thus many conceits that we today would define as confections or preserves were drugs or something close to drugs—we might call them nutraceuticals—in the medieval Islamic world. These conceits entered the Christian West through Arabic-language drug formularies and health handbooks (essentially herbals or books of simples) that were translated in Spain and Sicily. In the West, these conceits straddled the same odd conceptual fence that they did in the East, being both prescribed by physicians as well as eaten, particularly after meals, when they were believed to speed the digestion. Recipes for some of these nutraceuticals, including quince paste, fruits in sugar syrups, halva (made with starch or nuts, not sesame seeds), and marzipan (in Italian manuscripts), can be found in medieval European manuscripts primarily given over to food recipes. Most, though, are outlined in medical recipe books, including sugar work (fondant, taffy, and hard candy), gingerbread (nothing like today’s gingerbread), gum paste, dragées, candied citrus peel, and crystallized flower petals and herb leaves.

2.

The advent of the new haute cuisine in England can be dated with fair assurance to circa 1180, when a consortium of merchants dealing in the importation of spices and sugar was formed under the name of the London Pepperers and sugar is listed for the first time in the household accounts of the English king. Two English manuscript cookbooks, both in Anglo-Norman, were written in the thirteenth century, many more, in Chaucerian Middle English, in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Many of the recipes in the English cookbooks also appear, in some form, in medieval French cookbooks, such as the famed Viandier attributed to the French court cook known as Taillevant. Given the international prestige of French cooking since the mid-seventeenth century, it is not surprising that many writers have assumed that the French developed these recipes and the English merely adapted them. However, there are many reasons to suppose that the exchange went in both directions.

The elite medieval English dinner was served in two principal courses or, on grand occasions, three, each typically comprising four to six dishes, though more, perhaps many more, if the dinner were a feast. In most surviving menus, at least half of the total dishes comprise plain boiled, baked, or roasted meat or fish, the larger, more substantial cuts featured in the first course, the smaller or more delicate ones in the second and optional third. In a manuscript penned around 1420, the more complex dishes of the cuisine are divided into three categories: pottages (potages), sliceable foods (leche metys), and baked foods (bake metys). By far the largest category, pottages were all dishes with a liquid or runny consistency, including thick soups, boiled foods served in their cooking broths, porridges (like blancmange), stews, sauced dishes on toast, aspics, and hashes. Sliceable foods comprised foods that had defined shapes, such as pastas, pancakes, fritters, blood puddings, haggis, forcemeats, and pressed-curd dishes. Baked foods were pies and tarts, whose tough crusts were considered mere baking containers for the filling and were often discarded or doled out to the poor after they were emptied. Only a few of the complex dishes occupied prescribed courses in the medieval English dinner. However, as a group, the progression of these dishes mirrored that of the plain meats and fish, in that the more delicate, often sweeter ones, such as small fowl, shellfish, fruited forcemeats, pancakes, fritters, and little custard tarts, tended to cluster in the second and third courses.

Following the two (or three) principal courses a little digestive course was served, consisting of the sweetened, spiced wine called hippocras and sweetened, spiced iron-baked wafers. After the wafers had been nibbled, a prayer was said and plain spices and so-called comfits were brought out, the latter comprising sugared tidbits such as candy-coated spices (or seeds or nuts), preserved ginger, candied citrus peel, and crystallized flower petals and herb leaves. In great households, the elite company retired to a specially designated room to consume the spices and comfits, where they enjoyed a voidee, so named because it voided, or cleared, the site of dinner (usually the great hall) of people.

Our Morgan dinner was based on an Eastertime menu that appears in MS Cosin V.III.11, now in the possession of the Durham University Library, in Durham, Britain. The advantage of this menu is that it is atypically scant in plain boiled, baked, or roasted meats, which no longer impress in today’s protein-plentiful world. Also, unlike most, this menu does not include any birds that we no longer regard as edible, such as swans (a particular medieval English favorite), herons, cranes, sparrows, larks, plovers, and pewits.

In Paschal tempe flesshedays

Þe fyrste cours: creteyne to potage & pygges in sawse sauge þerwith, smale felettes indorretes & þerwith cometh smale pertriche ibake & checkones. Þe ii cours: bruet saraseyns þerwith gele & capouns dorres, lechefres & small rost. Þe iii cours: dariol of crem & of refles togedere.

For various reasons, explained below, the menu that we actually served differed somewhat from the MS Cosin menu:

Feste for þe Morgan

Þe fyrste cours: creteyne to potage & pygges in sawse sauge þerwith, mouton with frumente, sawse camelyne, smale checkones ibake with black sauce. Þe ii cours: bruet saraseyns þerwith gele of fyssh, tart de Bry & blank maunger. Þe iii cours: dariolles & fretoure togedere, comadore & yrchon. Finis: ypocras & wafres, marchpane & confyts dyvers.

My source for the MS Cosin menu and many of the recipes I prepared was Curye on Inglisch, a collection of four medieval English recipe manuscripts, with extracts from several others, compiled and edited by Constance B. Hieatt and Sharon Butler (Oxford, 1985). I also used recipes from Two Fifteenth-Century Cookery Books, a collection edited by the English scholar Thomas Austin and published in 1888. Both collections include extensive glossaries of terms, which are erudite, clearly written, and extremely helpful. (Although written a century apart, the two books agree on almost all major points.) In addition, I consulted several manuscripts translated and extensively annotated by Terrence Scully, including The Viandier of Taillevant (University of Ottawa Press, 1988) and The Neapolitan Recipe Collection, a medieval Italian manuscript (MS Buhler 19) in the possession of the Morgan Library (University of Michigan Press, 2000).

Here are the recipes for the dishes we served (transcribed into contemporary English), with their sources and some brief notes. My interpretations of the recipes can be found here.

Craytoun

For to make craytoun (MS Douce 257; Hieatt): Scald chickens, then boil them. Grind ginger or pepper, and cumin, and temper with good milk. Add the chickens and boil them, and serve it forth.

Recipes called craytoun (in various cognates) turn up in both French and English sources. Scully derives the name from Old French cretonnee, meaning fried, but frying is not involved in this or most other variants. Oddly, the common element among the recipes, says Hieatt, is that most involve milk. The dish is suggestive of a cumin-scented curry. Perhaps this is coincidental, for I find no eastern precedent for the dish in the Baghdadi or Andalusian cookbooks. In the regrettably dark photo, the little dots are pomegranate kernels, a favorite medieval English garnish. This dish, like many others in this menu, is golden in color. Perhaps this has something to do with Easter, which is associated with the rising of the (golden) sun.

Pygges in sawse sawge

Pygges in sawse sawge (Forme of Cury; Hieatt): Scald and quarter suckling pigs and simmer them in water and salt. Drain them and let them cool. Grind parsley and sage with bread and the yolks of hard-boiled eggs. Add vinegar, leaving the mixture somewhat thick. Lay the suckling pigs in a vessel, cover with the sauce, and serve it forth.

Raw green sauces, all fairly similar, are outlined in medieval English, French, Italian, and Catalan manuscript cookbooks. There is also a recipe in the ancient Roman cookbook attributed to Apicius but none in the Baghdadi or Andalusian cookbooks, so perhaps the idea is western. This sage-intensive version is delicious and very much worth making. I substituted pork tenderloin for the pigs and decorated the dish with the whites of the eggs, a garnish suggested in several medieval English recipes.

To make frumente (Forme of Cury; Hieatt): Bray clean wheat well in a mortar [to remove the hulls]; boil it in water until the grains crack. Drain it and let it cool. Mix it with good both and sweet cow’s milk or almond milk. Add raw egg yolks and saffron and salt it; don’t let it boil after the egg yolks are added. Put it in dishes with venison or fat fresh mutton.

Mouton with frumente

I find the smale felettes indorretes (fried pork fillets in a golden batter) listed in the first course of the MS Cosin menu a dull dish. So, for our Morgan dinner, I replaced it with another dish listed in the first course of several medieval English menus: roasted venison or mutton served with a creamy wheat-berry pottage. (My roast was lamb.) The name of the pottage derives from Old French froument, or grain. The dish is pretty, if rather bland, or so I thought (others liked it better). A recipe that I recently came across in a manuscript in the Folger collection supports my long-held suspicion that this pottage was the inspiration behind the dessert called barley cream, extant in England and America from the late seventeenth into the early nineteenth centuries.

Sawse camelyne (Forme of Cury; Hieatt): Take currants and shelled nuts [likely walnuts] and crusts of bread, and ground ginger, cloves, and cinnamon; bray it well in a mortar and add salt. Mix it with vinegar and serve it forth.

This delicious sauce was beloved throughout medieval Europe. It some households, it was set out at all dinners as an all-purpose condiment. I intended it for the lamb roast. It is also lovely with any cold meat. Hieatt believes that the name derives from Anglo-Norman canel, meaning cinnamon, though others connect the name to the sauce’s brown color, like that of a camel. This sauce is similar to several outlined in the ancient Roman cookbook attributed to Apicius, though none of the Roman sauces contain cinnamon, which Apicius seems barely to know. In contrast, there are 289 references to cinnamon in The Andalusian Cookbook.

Smale checkones ibake with black sauce

Black sauce for capouns y-rostyde (Ashmole 1439; Austin): Take capon livers and roast them well. Take anise, ground Paris ginger, and cinnamon, and a little bread crust [likely toasted] and grind them all together well. Temper it with verjuice and capon fat, and then boil it and serve it forth.

Instead of serving plain baked partridges and chickens in the first course, as the MS Cosin menu seems to indicate, we served Cornish game hens (likely similar in size to medieval chickens) with this piquant liver sauce. The anise-cinnamon seasoning, as well as the texture, color, and general intensity of the sauce, are suggestive of certain Mexican moles, but I do not find a similar preparation in The Andalusian Cookbook. Perhaps the sauce is western, for some versions call for blood rather than liver, and blood was forbidden in Islamic cooking.

Bruet sarcynesse

For to make a bruet of sarcynesse (MS Douce 257; Hieatt): Cut fresh beef into pieces and fry it with bread in fresh grease. Take it out, dry it [drain the fat], and put it in a pot with wine, sugar, and ground cloves. Boil everything together until the beef has absorbed the liquid. Boil almond milk and [whole] cubebs, mace, and cloves together. Add the meat and put it in a serving dish.

This rich, fragrant, gently sweet-sour “Saracen” stew strikes me as similar to Thai “Massaman” (Moslem) beef curry. In the making of both dishes, the braising medium is cooked down until the meat begins to fry in its own fat, whereupon almond milk or coconut milk is added to bloom a sauce. Both dishes have a similar flavor, despite the lemon grass and other Southeast Asian seasonings added to the Thai version. You don’t absolutely need the hot, astringent cubebs, but you do need almond milk, and the ersatz stuff in the carton will not do.

Gele of fyssh

Gele of fyssh (Forme of Cury; Hieatt): Cut tench, pike, eels, turbot, and plaice in pieces. Scald them, wash them clean, and dry them with a cloth. Place them in a pan and cook them in half vinegar and half wine. [Remove the fish from the broth] and pick out the bones. Strain the broth through a cloth into an earthen pan and add sufficient ground pepper and saffron. Bring the broth to a simmer and skim it well. When it is boiled [reduced sufficiently to jell], remove the grease. Arrange the fish on platters, strain the broth over them through a cloth, and serve the dish cold.

The gele listed in the second course of the MS Cosin menu could be either meat or fish in aspic. I chose fish for our Morgan dinner. Loosely following the recipe above, I poached salmon in white wine, white wine vinegar, and seasonings, and then stiffened the broth with packaged gelatin. The delightful pale garnish of paper-thin “leaves” of fresh ginger and slivered almonds, vaguely visible in the photo, is called for in a recipe for jellied fish outlined in Harleian MS 4016 (in Austin). Meat and fish jellies appear in many medieval European menus. The Neapolitan Recipe Collection shows that the fifteenth-century Italians were already coloring and (probably) sweetening jellies and molding them in elaborate shapes, sometimes omitting the meat. The English soon enough followed suit.

Tart de Bry

Tart de Bry (Forme of Cury; Hieatt): Make a crust one inch deep in a pan. Mix raw egg yolks and ruayn cheese [a semi-soft fat autumn cheese, per Hieatt], and add ground ginger, sugar, saffron, and salt. Put the mixture in the crust, bake it, and serve it forth

In medieval English cookbooks, lechefres, listed in the second course of the MS Cosin menu, is sometimes a tart of ground dried fruits and sometimes a tart of cheese, although, as Hieatt points out, neither makes sense, as the title implies a sliced food that is fried. For our Morgan dinner I opted for a cheese tart and, for fun, used a recipe with the word Bry (Brie) in the title, which is virtually identical to the recipe for the cheese tart called lese fryes in Harleian MS 4016 (in Austin). According to Hieatt, the cheese intended may have been similar to modern Pont-l’Évêque, for which I substituted Saint Nectaire. A well-ripened Brie or Camembert will also work. The tart is a bit like a puffy cheese omelet in a crust. Medieval English cooks made pastry with pasta dough, and wresting an edible tart crust from pasta dough is, in my view, a fool’s errand. I use a modern recipe. Similar cheese tarts survived in the Netherlands into the seventeenth century and are depicted in period Dutch paintings. Dutch-American culinary historian Peter Rose covers the Renaissance Dutch cheese tart with whole almonds, a very nice touch.

Blank maunger

Blank maunger (Forme of Cury; Hieatt): Simmer capons, and then drain them. Grind blanched almonds and mix them with the capon broth. Pour the almond milk into a pot [after straining out the almonds]. Add washed rice and let it simmer, then tear the breast meat of the capons in small pieces [strings] and add it, along with white grease, sugar, and salt. Let it simmer [until quite stiff]. Serve it forth, decorated with red or white anise comfits and almonds fried in oil.

Since I inserted a roast in the first course of my Morgan menu I omitted the smal rost (likely a pork or mutton leg, Hieatt speculates) listed in the second course of the MS Cosin menu and served blank maunger instead. This famous pottage (or one of its variants) appears in the second course of many other medieval English menus, and I thought that guests should have a chance to taste it. The dish is much like rice pudding, except not as sweet and with chicken in it. I adore it. Per the recipe, I garnished the dish with aniseed comfits, which are available from online Dutch import shops under the De Ruijter brand.

Dariolles

Dariolles (Harleian MS 4016; Austin): Take wine and fresh broth, whole cloves and mace, bone marrow, powdered ginger, and saffron, and let them boil together. Take cream (strained if clotted) and egg yolks and mix them together, and then add the liquid in which the bone marrow was boiled. Then make crusts of fine paste, and put the marrow into them [apparently unmelted marrow skimmed from the spiced liquid], along with minced dates and strawberries, if they are in season. Set the crusts in the oven and let them bake a little while, and then take them out, pour in the cream mixture, and bake them enough [until the custard sets].

Medieval English dariols were small custard tartlets of varying composition. The word, according to Terrence Scully, is French and designates a large pastry crust in medieval French sources. How it came to mean small custard tartlets in England is unknown. I had previously tried a very simple recipe for dariols outlined in Forme of Cury, which calls for a filling of cream, egg yolks, sugar, and a little saffron for color. The tartlets were perfectly nice but not terribly interesting, so for our Morgan dinner I followed the recipe above instead. The wine infusion imparted little flavor to the custard (even though I used quite a bit of spice), and the marrow was nuisance (as it always is). But I learned something very useful. I cut supermarket strawberries in pieces the size of fraises de bois and put three pieces in each tart shell, along with a couple of teaspoons of minced dates and some crumbled marrow, and then baked the shells until firmed and browned, as the recipe intends. To my surprise, the strawberries desiccated rather than dissolving into a pulpy mush, becoming little pinpoints of intense strawberry flavor in the bland, rich custard. Also unanticipated, the strawberries and dates were a lovely match. The lesson (which I often have to force myself to follow) is always to do what the old recipes say, no matter how weird or wrong it seems.

Fretoure

Fretoure (Harleian MS 279; Austin): Take wheat flour, ale yeast, saffron, and salt and beat everything together as thick as batters should be made on days when meat is permitted. Then take good apples and cut them in the proper way for fritters, and thoroughly wet them in the batter. Fry them in good oil, put them in a dish, sprinkle them with sugar, and serve them forth.

Hieatt speculates that the mysterious refles in the third course of the MS Cosin menu may designate some sort of fritter. If so, many medieval cooks probably chose apple fritters, which were great favorites throughout Europe. This is an excellent recipe.

Comadore

Comadore (Forme of Cury; Hieatt): Take figs and raisins. Pick them [seed the raisins], wash them clean, and scald them in wine; grind them quite small. Dissolve some sugar in the wine used to scald the fruit. Strain the wine and mix the fruit with it. Peel some good pears and apples and take the best part of them [core them]. Grind them small and mix with the raisin mixture. Set a pot on the fire, add some oil, and pour the mixture in it, and stir carefully and keep it from burning, and add ground ginger, cinnamon, and galingale and whole cloves, cinnamon, and mace. Add pine nuts lightly fried in oil and salt. When it is fried enough, put it into a bowl and let it cool. When it is cold, cut it with a knife into small pieces the width and length of a little finger, and wrap it tightly in good pastry, and fry them in oil, and serve them forth.

Comprising only two dishes, the third course of the MS Cosin menu struck me as anticlimactic. So, for our Morgan dinner, I added two additional dishes, both typical in the third course of other period menus. Hieatt suggests that the dish called comadore may derive its name from the Spanish comedar, meaning glutton or ‘fit for an epicure.’ If so, the name is apt. These filled fritters are fabulous, something like crispy Fig Newtons with spices. The “good pastry” indicated is actually pasta dough, for which I substituted egg roll skins. Wonton wrappers might be better.

Yrchon

Farsur to make pomme dorryse and oþere þynges (Forme of Cury; Hieatt): Take raw pork meat and grind it small. Mix it with eggs and strong spice powder, saffron and salt, and add raisins and currants. Make it up into balls, wet the balls well with egg white, and cook them in boiling water. Take them from the water and put them on a spit. Roast them well, strain ground parsley with eggs and a portion of flour, and let the batter run about the spit. And if you wish, use saffron in place of parsley, and serve it forth.

This is the first of five recipes in Cury outlining fanciful conceits made from fruited pork forcemeats: gilded “apples”(the pomme dorryse of the recipe title), a stuffed “cokantrice,” “hedgehogs” stuck with almond “quills” (the yrchon of our Morgan menu), “flower pots” planted with planted with “flowers,” and little “cloth sacks.” Except for the sacks, all of these conceits appear in the Viandier of Taillevent (although in somewhat different forms). Fruited, spiced meatballs are a feature of several contemporary Middle Eastern cuisines (though with lamb or beef, not pork) and also of contemporary Italian (especially Sicilian) cooking. (The canonical Italian cookbook author Artusi also has a recipe, which is adapted in Lynne Rossetto Kasper’s The Splendid Table.) This leads one to think that the idea originally came from Islamic Spain or Sicily, but I do not find a recipe in the Baghdadi or Andalusian cookbooks, and there are none in the medieval Italian manuscripts with which I am familiar (although the stuffing for a kid outlined in The Neapolitan Recipe Collection is similar). Wherever this forcemeat came from it is delicious.

Ypocras & wafres with marchpane

To Make Ipocras (Robert May, The Accomplisht Cook, 1665): Take a pottle [2 quarts] of wine, an ounce of cinnamon, an ounce of ginger, an ounce of nutmegs, a quart of an ounce of cloves, seven corns of pepper, a handful of rosemary-flowers, and two pound of sugar.

The MS Cosin menu does not indicate a final course of digestive sweets, nor do most other period English menus, probably because it was routine. The course always included hippocras, named for the ancient Greek physician Hippocrates, the putative “father” of humoral medicine. Hippocras was made by steeping wine, typically white, with spices and sugar, which were thought to “warm” the stomach and thus facilitate digestion. The medieval recipes call for ground spices, which absorb a great deal of the wine and take forever to filter out. The seventeenth-century English, wisely, used crushed spices instead and so do I. Fresh ginger and dried rosemary leaves make perfectly fine substitutes for whole dried gingerroot and rosemary flowers. This is an irresistible after-dinner drink.

To make wafers (Gervase Markham, The English Hus-Wife, 1615): To make the best wafers, take the finest wheat flour you can get, and mix it with cream, the yolks of eggs, rose water, sugar, and cinnamon till it be a little thicker than pancake batter; and then, warming your wafer irons on a charcoal fire, anoint them first with sweet butter, and then lay on your batter and press it, and bake it white or brown at your pleasure.

Although wafers were as essential to the digestive course as hippocras, I have not found a medieval English recipe for them, perhaps because they were more often bought than made. For our Morgan dinner I followed Gervase Markham’s recipe in The English Huswife (1615). By Markham’s time wafers were customarily rolled, like those in the photo, but they may have been left flat in the Middle Ages. Wafers are lovely but they must be baked in an iron, either stove-top or electric, and are a tedious, finger-burning project.

The other sweet seen in the photo is marzipan, which entered the English language as marchpane (in various spellings). The earliest reference to marchpane cited by OED (from 1492) implies a particular marchpane conceit that was highly fashionable in England through the mid-seventeenth century: a thin cake about fourteen inches across, which was lightly baked, glazed with a white sugar icing, and often elaborately decorated. I formed the marchpane for our Morgan feast likewise. England and the rest of Europe learned about marzipan from the Italians, who loved it. The Italians got it from the East. It turns up in numerous guises, in meat and fish dishes as well as sweets, in both the Baghdadi and Andalusian cookbooks.

Did the medieval English privileged eat like this everyday? It’s a logical question to ask but not really the right question. Medieval meals were structured differently from ours. With a few exceptions (such as frumenty with venison or mutton), medieval dishes did not “go together,” as in a “main dish” and “sides.” Rather, dishes were perceived as separate, and people sampled only those that appealed them. (The phrase “þerwith cometh” on the MS Cosin menu likely indicates that two dishes were meant to be set on the table at the same time, not that they were meant to be eaten together.) In addition, only the lord and lady, their family, and honored guests were entitled to be served all of the dishes featured on surviving period bills of fare. Lower-ranking members of a household were served only the plainer, cheaper dishes, and the lowliest may have had to content themselves with gruel-like pottages and leaden dark breads. Needless to say, all seventeen guests at our Morgan feast were served all of the dishes (in two separate messes, to minimize the passing of heavy platters), and they proved to be hardy trencher-persons. A few even had second helpings of the apple fritters!

- A caveat: All forms of writing became more common starting in the twelfth century than previously.

- Blancmange (in various cognates), or “white dish,” was the most important of these dishes. Beloved throughout Europe, blancmange was a stiff porridge of rice (unknown in Europe prior to Islamic contact), teased poultry breast, and almond milk, liberally seasoned with sugar. Several variants on blancmange, some with explicit Arab links in their names, also abound in medieval English recipe manuscripts and feast menus. The dish is still made, in quasi-medieval form (with chicken), in Turkey today. And then there is pasta, which appears in many forms in medieval manuscript cookbooks, including English ones. There is persuasive evidence that pasta may be a gift of the East, although, if it is, it likely entered Christian European cooking well before the twelfth century.