Two and a half years ago I came across a manuscript cookbook at the Clements Library, of the University of Michigan, at Ann Arbor, that immediately brought Mary Randolph and Hess’s commentary on her back to mind. Titled Receipts in Cooking, this manuscript was “collected and arranged” (says the title page) for one Mary Moore, in 1832. Moore hailed from somewhere in the Deep South, likely Georgia or Mississippi, but I would barely have guessed this from her cookbook. I could find only fifteen dishes peculiar to the South among the book’s eighty-four recipes. The rest, I knew, were common in the North too, for I had seen them repeatedly in antebellum northern cookbooks. And, like The Virginia Housewife, Moore’s sixty-nine nationally popular dishes were overwhelmingly English. Only seven were American specialties, such things as pumpkin pie, soda-leavened cakes, and cornbread.

The resemblance between Receipts in Cooking and The Virginia Housewife, it turned out, was not coincidental. Fifty-six of Moore’s recipes—or two thirds of the total—were copied, verbatim or nearly so, from Mary Randolph. I understood why nearly all of Moore’s distinctively southern recipes were taken from The Virginia Housewife, for it was the only available printed source for such recipes in 1832. But I wondered why fifty-seven of Moore’s English recipes were also cribbed from The Virginia Housewife rather than from one of the English cookbooks that supplied another fourteen of Moore’s recipes. 1 Was Randolph chosen merely out of convenience or sentiment? Or did she handle English cooking in uniquely southern ways, in which case Hess might be right?

In fact, Randolph’s interpretation of English cooking proved to differ in no significant way from that “A Boston Housekeeper” (Mrs. N. K. M. Lee), author of The Cook’s Own Book, published 1832, which contains all but four of the English dishes copied from Randolph in the Moore cookbook. Here, for example, are the recipes of Mrs. Lee and Mary Randolph (and Mary Moore) for beef olives, or stuffed beef roulades served in brown gravy. 2

Beef Olives

The Cook’s Own Book, 1832

Cut the beef into long thin steaks; prepare a forcemeat made of bread-crumbs, minced beef suet, chopped parsley, a little grated lemon-peel, nutmeg, pepper, and salt; bind it with the yolks of eggs beaten; put a layer of it over each steak; roll and tie them with thread. Fry them lightly in beef dripping; put them in a stewpan with some good brown gravy, a glass of white wine, and a little Cayenne; thicken it with a little flour and butter; cover the pan closely, and let them stew gently an hour. Before serving, add a table-spoonful of mushroom catchup; garnish with cut pickles.

Beef Olives

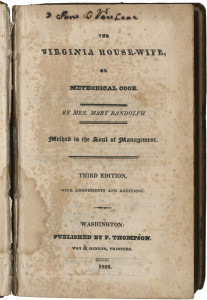

The Virginia Housewife, 1824

Cut slices from a fat rump of beef six inches long and half an inch thick, beat them well with a pestle, make a forcemeat of bread crumbs, fat bacon chopped, parsley a little onion, some shred suet, pounded mace, pepper and salt; mix it up with the yolks of eggs, and spread a thin layer of each slice of beef, roll it up tight and secure the rolls with skewers, set them before the fire, and turn them till they are a nice brown, have ready a pint of good gravy thickened with brown flour and a spoonful of butter, a gill of red wine with two spoonsful of mushroom catsup, lay the rolls in it and stew them till tender: garnish with forcemeat balls. (See adaptation.)

There are, to be sure, minor discrepancies between these two recipes, but these cannot be attributed to differences between northern and southern styles of cooking (not that the recipes imply such differences) but rather to the fact that the two authors worked off different English sources. I have not been able to identify the English source of Mrs. Lee’s recipe, but I know there is one, for Mrs. Lee explicitly acknowledges that she copied almost all of her recipes from previously published cookbooks, and there was no American cookbook yet in print in which she could have found her beef olives. I do know the English cookbook from which Mary Randolph paraphrased her recipe. It is The Experienced English Housekeeper, published in 1769 by Elizabeth Raffald, a fancy caterer and gourmet food shop proprietor. In editing out the phrases “penny loaf” and “tossing pan” Randolph has Americanized the language of Raffald’s recipe, and in substituting bacon and suet for marrow she has modernized it. I do not know the reason for Randolph’s other minor changes, but I do not believe that any were meant to make Raffald’s English recipe more southern American.

Beef Olives

The Experienced English Housekeeper, 1769

Cut slices off a rump of beef about six inches long and half an inch thick. Beat them with a paste pin and rub them over with the yolk of an egg, a little pepper, salt, and beaten mace, the crumbs of half a penny loaf, two ounces of marrow sliced fine, a handful of parsley chopped small and the out rind of half a lemon grated. Strew them all over your steaks and roll them up, skewer them quite close, and set them before the fire to brown. Then put them into a tossing pan with a pint of gravy, a spoonful of catchup, the same of browning, a teaspoonful of lemon pickle, thicken it with a little butter rolled in flour. Lay round forcemeat balls, mushrooms, or yolks of hard egg.

Although I sense the stirrings of “an authentic American cuisine” in The Virginia Housewife, I believe that Randolph’s cooking remains essentially English. Actually, Hess seems very nearly to believe the same. She declares that the “warp” of Randolph’s cooking is English, and she observes, correctly, that “there are English recipe titles by the score in The Virginia House-wife.” Hess would certainly know: she was, and still is, the greatest American scholar of early modern English cooking. “But there are surprises,” says Hess—by which she means, primarily, a weft of peculiarly southern non-English influences interwoven with the English warp, creating a unique southern cloth. But her thinking about these “surprises” is not always persuasive.

Popular historical accounts maintain that critical influence on southern cooking was exerted by the French—the Creole and Acadian French of Louisiana, the Huguenot refugees of the Carolinas, and, preposterously, Thomas Jefferson, who was not French of course, but who traveled to France, served French dishes and French wines at his dinner parties, and had a French maître d’ at the White House, and who, therefore, is inferred to have somehow introduced French cooking to the South, indeed to America. Hess is properly dismissive of all this, writing that Randolph’s French-titled dishes—and there are dozens of them, eleven of which show up in the Moore cookbook—had been naturalized in England for a century or more by the time Randolph outlined them (and Jefferson served them to his guests). Hess cites as an example Randolph’s recipe for beef à la mode, which had already made regular appearances in English cookbooks since the early eighteenth century. 3

But Hess, oddly, falls into a trap that popular historians have set. Rarely bothering to study period recipes, the popularizers endlessly repeat the tired wisdom that historical English food was “bland and boring.” Some of it was, but not all—not many of the finer dishes favored by the sophisticated and the privileged. So while Hess is correct to point out the Englishness of beef à la mode, she is in error when she then goes on to state that Randolph must have imported her particular “wonderfully redolent” recipe for this dish directly from a French cookbook. Randolph’s recipe calls for two heads of garlic, and according to Hess, English recipes for beef à la mode had been “innocent of garlic all through the eighteenth century.” In fact, Randolph copied her recipe, including the garlic, virtually verbatim from one of her favorite English sources, The Experienced English Housekeeper. In a similar vein, Hess seems to imply—her phrasing is not clear—that Randolph’s recipes for four especially sophisticated conceits, Fondus, Bell Fritters, Matelote, and To Fry Sliced Potatoes (authentic French fries, claims Hess), are likewise direct French imports. Actually, all of these dishes can be found in eighteenth-century English cookbooks, three of them in The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy, a cookbook that virtually every elite antebellum southern household owned. Generally speaking, Hess gives historical English cooking a fair appraisal, but her thinking here seems to have been infected by popular tropes.

Two other groups often imputed to have given southern cooking its unique character are American Indians and African slaves. Hess has little to say about Native American contributions, as these were mostly a matter of corn, and as crucial as corn was to the evolution of southern cooking, it was crucial to northern cooking too. Hess gives more consideration to the contributions of the enslaved, and justifiably so. She is right to point out African and African-Creole influence in southern dishes such as gumbo and pepper pot, as well as in typical southern foods like peanuts, sesame seed, watermelon, and yams. But Hess’s argument in favor of an African contribution to southern seasoning is dubious. Hess asserts that many of Virginia’s enslaved black cooks, having passed through the West Indies, picked up “tricks of seasoning from the exuberant Creole cuisines” of these places, which they then stirred into Virginian cooking pots. And thus, she writes, “Virginians had become accustomed to headier seasonings than were the English, or New Englanders, for that matter.” I am skeptical that “exuberant Creole cuisines” existed in the hellacious West Indies at the turn of the nineteenth century or that slaves in transit were in a position to absorb seasoning tips. But beyond that, the problem is that Randolph does not season her food any differently from Mrs. Lee, Eliza Leslie, and other tony antebellum northern cookbook authors. Randolph does call for cayenne frequently, but so do her northern counterparts, for cayenne was beloved in England: Raffald’s reliance on cayenne in The Experienced English Housekeeper is almost compulsive.

2.

Whatever they may promise, most regional cookbooks deliver more or less the same recipes that can be found in many other cookbooks, for in truth most places do not possess distinctive cuisines. Still, people buy these books because, for various reasons, they are attached to the places these books celebrate. We assume today that southern women bought The Virginia Housewife to learn the secrets of southern cooking. But my sense is that antebellum southerners were barely aware of their cuisine as distinctively southern and that they bought—or in the case of the Moore cookbook, copied—Randolph’s cookbook primarily because it was of Virginia. Throughout the antebellum South, diverse though it was, Virginia was regarded as the cradle of the American republic and the South’s ideological and cultural lodestar, the exemplar of the highest-flown ideals of the southern way of life—as lived, of course, by its most privileged white inhabitants—ideals later popularly embodied in the phrase “southern hospitality.” Whatever the actual appeal of The Virginia Housewife was in its day, regional cookbooks whose pull was primarily their place were already on the scene by the time of the Civil War. A case in point is The Great Western Cook Book, first published in 1851, at the height of western migration. Most of the book’s recipes are along the lines of Soup à la Jardinière, Chestnut Stuffing, Veal Croquettes, and Charlotte Russe, fare more likely encountered in a New York townhouse than a wilderness log cabin. To rescue the theme, the publisher decorated the title page with a vaguely western-looking motif and inserted a few recipes with cornball “western” titles: Soup—Rough and Ready, Steamboat Sauce, and Sausages—Hoosier Fashion. Similar strategies are still deployed by publishers today.

![grea001[1]](http://manuscriptcookbookssurvey.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/grea0011-214x300.gif) I suspect that few in 1851 believed that The Great Western Cook Book typified western cooking or that there even was such a thing. But by the middle of the last century, the food publishing industry had managed to convince the public of the actual existence of regional cuisines that, in fact, the industry had largely invented. Famous, and appealing, examples of this sleight of hand are the five volumes in the Time-Life series “American Cooking,” published between 1968 and 1971. The general volume, titled simply American Cooking, and the southern volume are plausible, but the other three—The Northwest, The Great West, and The Eastern Heartland—make a far less convincing case for the distinctiveness of their respective cuisines. Actually, Time-Life would have us believe that there are twelve American regional cuisines altogether: the general volume delineates them in a color-coded map. Absurd though such formulations may be, they served clever marketing purposes. At mid-century, regional cookbooks endowed American cooking with a richness, diversity, and historical pedigree equal to that of French cuisine, thereby appealing to those alienated by the then-rampaging popularity of a foreign, highfalutin culinary fashion. Even more importantly, regional cookbooks materialized a dignified, wholesome American food culture separate from its modern mass incarnation, appealing to those who despised modern mass food as the degraded product of big business interests. At the risk of second-guessing Karen Hess, who is no longer living to speak for herself, I suspect that her notorious contempt for the national food scene of her time, in its diverse manifestations, lured her into framing The Virginia Housewife as embodying a more distinctive southern cuisine than it actually did.

I suspect that few in 1851 believed that The Great Western Cook Book typified western cooking or that there even was such a thing. But by the middle of the last century, the food publishing industry had managed to convince the public of the actual existence of regional cuisines that, in fact, the industry had largely invented. Famous, and appealing, examples of this sleight of hand are the five volumes in the Time-Life series “American Cooking,” published between 1968 and 1971. The general volume, titled simply American Cooking, and the southern volume are plausible, but the other three—The Northwest, The Great West, and The Eastern Heartland—make a far less convincing case for the distinctiveness of their respective cuisines. Actually, Time-Life would have us believe that there are twelve American regional cuisines altogether: the general volume delineates them in a color-coded map. Absurd though such formulations may be, they served clever marketing purposes. At mid-century, regional cookbooks endowed American cooking with a richness, diversity, and historical pedigree equal to that of French cuisine, thereby appealing to those alienated by the then-rampaging popularity of a foreign, highfalutin culinary fashion. Even more importantly, regional cookbooks materialized a dignified, wholesome American food culture separate from its modern mass incarnation, appealing to those who despised modern mass food as the degraded product of big business interests. At the risk of second-guessing Karen Hess, who is no longer living to speak for herself, I suspect that her notorious contempt for the national food scene of her time, in its diverse manifestations, lured her into framing The Virginia Housewife as embodying a more distinctive southern cuisine than it actually did.

Everyone would agree that by 1984, when the facsimile edition of The Virginia Housewife was published, southern cooking had long since coalesced into “an authentic American cuisine” with local variations. But the cookbooks tell us that this turning point came after the Civil War, when the humiliated South retrenched in self-flattering fantasies of the old southern way of living. As Eugene Walter, an Alabama native, observes in Time-Life’s American Cooking: Southern Style, the post-war South “took its tone, set its style, cocked its snoot, decided to become set in its ways and pleasurably conscious of being so. . . glamorizing its past and transforming anecdote into legend.” And among the old “rites and observances” to which the South clung, “none was more important than those of the table.”

The cooking of the antebellum South did change after the war, but not as much, and not in the same ways, as the cooking of the North. While the North borrowed liberally from the fashionable French cuisine of the Gilded Age and from the cooking of immigrant groups, the South tended to stick with dishes of the past, many of which were English: spiced beef (an iteration of beef à la mode), calf’s head variations, fricassees of all sorts, hashes and minces, meat collops, potted foods, drawn butter sauces, vegetable “mangoes,” multifarious pickles and ketchups, brandy peaches and other preserves, pones and other hot breads, pound cake, sweet potato puddings, boiled puddings, jelly cakes, cheesecakes (chess pies), syllabub, fruit and flower wines, and more. And while the North fell under the sway of so-called “scientific cookery,” the founding ideology of modern home economics, which taught a cheaper, simpler, lighter, plainer style of cooking, the South retained its allegiance to luxury, ostentation, richness, high seasoning, vinegar-sharpening, and tooth-aching sweetness. This is only part of a complex story, but it is the most crucial part: while the cooking of the North moved forward, becoming more modern and more distinctively American, the cooking of the South remained antique—and in many respects the better for it.

The astonishing southern cuisine that developed between the Civil War and the First World War was practiced by the extended family of Virginia Black smallholders into which the celebrated chef and cookbook author Edna Lewis was born in 1916. In What Is Southern?, an arresting essay that went unpublished until two years after her death, in 2006, Lewis answers her question with remarkable, resonant thoroughness, listing some four dozen dishes characteristic of the South and not of the rest of the country. Edna Lewis’s southern is sometimes described as “refined” in contrast to today’s more typical downhome, deep-fried, barbecue-with-sides southern or its upscale restaurant correlative, summed up by one wag as “I don’t know what southern cooking is, but I always know there will be corn in it somewhere.” But Lewis’s own perspective is that her southern is not so much refined as old-fashioned, in danger of ‘passing from the scene’ unless deliberately preserved. It is hard to disagree with her. In our time, much of Lewis’s lovely southern—turtle soup with turtle dumplings, baked snowbirds, braised mutton, wild pig with pork liver and peanut sauces, potted squab with the first wild greens, and fig pudding—can only be cooked as historical reenactment.

- I was able to trace six of these fourteen recipes to three English cookbooks that were popular in this country and had been published in American editions: E. Smith’s The Compleat Housewife (1729), Hannah Glasse’s The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy (1747), and the expanded edition of Dr. William Kitchiner’s The Cook’s Oracle (1822). I could not ascertain the origins of the remaining eight English recipes, but their language indicates with near certainty that they were indeed English and copied from print.

- When this dish debuted in English manuscript cookbooks, in the fifteenth century, the word was “aloes,” from the French alouettes, or larks, which the rolls were thought, fancifully, to resemble. (Culinary historian Peter Rose tells me that the Dutch call a similar dish “little finches.”) “Aloes” became “olives” in the sixteenth century.

- Randolph’s recipe To Harrico Mutton, which is copied in the Moore cookbook, illustrates the occasional complications of determining the origins of specific French recipes that appear in English-language cookbooks. Historically, this dish was known in France by two different names: “haricot” and “halicot” (both in various cognates). The latter name would seem to be more correct, as it derives, according to the 1984 Larousse, from the French verb halicoter, to cut in small pieces (as the ingredients in this dish are). But “haricot” (which now means green bean) is documented earlier, appearing in in the 14th century manuscript of Taillevent. When the English adopted the dish, in the sixteenth century, they called it “haricot” and I had always seen it thus in English and American sources into the 19th century. But I recently spotted the recipe as Hallico of Mutton in The Johnson Family Treasury, an 18th century English manuscript recipe book that has just been published (beautifully). Was “hallico” current in England in the 18th century? Or did the Johnson family get their recipe from a French source?

![Mary Randolph[1]](http://manuscriptcookbookssurvey.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Mary-Randolph1.jpg)