By Stephen Schmidt, with Elaine Leong

This post was written in collaboration with medical historian Elaine Leong and borrows from several of her online articles. Elaine received her doctorate in Modern History from the University of Oxford in 2006. She is currently in residence at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science (MPIWG), based in Berlin, Germany, where she recently completed a book titled Treasuries for Health: Making Recipe Knowledge in the Early Modern Household. Elaine is also a collaborator in The Recipes Project, which hosts a fascinating, wide-ranging blog focusing on historical medical recipes.

6th century copy of De Materia Medica by Dioscorides (40-90 CE), still a central text of early modern medicine

The 1916 autobiography of Dr. Edward Livingston Trudeau1 reveals the astonishing recentness of effective medicines. In 1882 Trudeau established the first American tuberculosis sanitarium at Saranac Lake, New York, where patients underwent a “rest cure” in the cold, clear air of the Adirondack Mountains. Unfortunately, this cure worked only for some and usually only for a time, and by the 1890s Trudeau realized that the disease would only be effectively treated when the bacteria that caused it were identified and medicines against these agents were developed. Amazingly, some of Trudeau’s physician colleagues scoffed at the notion that bacteria caused tuberculosis—or for that matter any disease. Given this state of affairs, it is unsurprising that Oliver Wendell Holmes, a physician of Trudeau’s day (as well as a famed jurist), commented, “If we doctors threw all our medicines into the sea, it would be that much better for our Patients and that much worse for the fishes.”

I often think of Holmes’s pithy remark when reading early modern medical recipes, which appear in many early modern manuscript cookbooks and which were also compiled in manuscript books devoted solely to medical subjects. These medicines are compounded in diverse forms—spirits, wines, waters, syrups, electuaries, pills, salves, and poultices—and are purposed for a variety of conditions, some relatively minor, like chapped hands, pimples, or “surfeit,” and others grievous, like “cancer of the breast” or “the bite of a mad dog.” Some of these medicines seem harmless and pleasant enough to take, while others sound perfectly horrid, containing urine, animal parts, or substances now known to be poisons. As a culinary historian, I can make little of sense these medicines, and given how “unscientific” (and sometimes dreadful) they seem I assume that the persons who took them would have been better off if they had tossed them to the fishes.

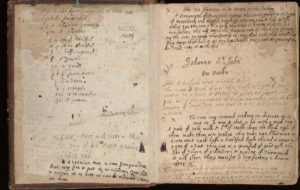

Johanna St. John Her Book (Wellcome Library MS 4338, digital images)

But the women who made these medicines in their homes clearly thought otherwise. In October 1711, Elizabeth Freke (1671-1714), a gentlewoman living in rural Norfolk, spent four days compiling a room-by-room inventory of “some of the best things” in her house. Written in a notebook containing her memoirs and her culinary and medical recipes,2 Freke’s inventory lists not only jewelry, clothing, furniture, linens, and kitchenware among her “best things,” but also 200 bottles of homemade medicines, which she kept in five locked cupboards in her private sitting room: “several bottles of cordiall water 114 quarts; of pintts of cordy water 36. And of the severall sorts of sirrups is 56 quarts and pints.” Another English gentlewoman, Johanna St. John (1631-1705), placed a similarly high value on her medical knowledge in a will she wrote out a few years before Freke compiled her inventory. Contemporary readers find nothing surprising in the bequests of valuable possessions that St. John made to beloved heirs: her Bible to her eldest son, various pieces of furniture, paintings, and silver to her daughters and granddaughters, and small gifts of cash and linens to old, loyal servants. But we do find it somewhat odd that St. John also made space in her will for her two manuscript recipe books: a book of “receipts of cookery and preserves,” which she left to her “granddaughter Soame,” and her “great receipt book,” an alphabetically organized compendium of remedies, which she bequeathed to her daughter Cholmondley. Few people today think to preserve their personal recipe collections for posterity, but St. John considered hers gifts of great value.

Recipes had been written since antiquity. But the avid trading of recipes and the compilation of recipe books in English homes was a distinctly early modern phenomenon, promoted by England’s impressive literacy rate, including among women, and its relatively fluid society, where moving up by acquiring knowledge was a realistic possibility. A gentlewoman like St. John could find recipes from many sources. Quite possibly she had inherited recipe books from family ancestors, just as her descendants would inherit recipe books from her. Because she was a wealthy woman, she likely owned printed recipe books (then expensive) that she could copy, and she could readily borrow more such books from people she knew. Her family, friends, and acquaintances, too, had recipes. If St. John was like other gentlewomen, she collected culinary recipes primarily from those of her own social rank or higher, whose taste and judgment she respected—and she was particularly interested in culinary recipes said to originate with titled individuals, whose rank implied connections with the court, where fashions were set. St. John’s medical recipes may have been culled from a more diverse network, for cures that worked for the humble also worked for the privileged.

Johanna St. John Copyright Lydiard House / Supplied by The Public Catalogue Foundation

St. John was likely aided in her search for recipes by other members of her household. These helpers probably included some of the men of her family, for many early modern men were avid recipe collectors. The letters of the third Viscount Edward Conway (c.1623-1683) and his nephew Edward Harley (1624-1700) show that the two men extensively exchanged and discussed both culinary and medical recipes during the 1650s. And many men compiled manuscript recipe books, especially during the second half of the seventeenth century. Sir Peter Temple of Stanton Bury (1613-1660) created bespoke recipe books for his daughter Eleanor, and the manuscript cookbook of Sir Kenelm Digby (1603-1665) became a huge bestseller when it was posthumously published by Digby’s assistant in 1667.

Given the faith that St. John placed in her recipe books, we can assume that she submitted her recipes to proof. It is unlikely that St. John personally tried the culinary recipes she collected in the manor kitchen—her cooks would have done that. But she likely did test the medical recipes herself, if with the aid of servants, for medicine-making, with its expensive ingredients, complex procedures, and high stakes, was regarded as a gentlewoman’s personal responsibility. If St. John’s manor was like other fine homes, it was built with a designated stillroom, and this is where she prepared her medicines.3 The stillroom was equipped with apparatus for distilling spirits, wines, syrups, and waters (Elizabeth Freke, unsurprisingly, owned extensive distilling equipment) and a waist-high charcoal brazier, or chafing dish, for procedures that required heating. The stillroom was attached to a stove room, a small chamber outfitted with slatted shelves and some sort of furnace, to which items were remanded that required drying or that needed to be kept dry during storage. Once a recipe had been made, it was evaluated by the household collective. If the results were poor, the recipe was rejected. But if the recipe worked, it was judged suitable for inclusion in the household recipe book, perhaps with modification. The modification process can sometimes be glimpsed on the pages of recipe books, in corrections or comments inserted by the writer.

Woman distilling, frontispiece of “The Accomplished ladies rich closet of rarities,” 1691, Credit: Wellcome Library, London.

Culinary historians can readily believe that St. John’s culinary recipes, if conscientiously tested and copied, actually worked—and still work today, as many early modern culinary recipes do, often in fascinating ways that confound contemporary expectations. But could any of St. John’s medical recipes possibly cure, given their “unscientific” basis? In her gloss of the Eleanor Fettiplace recipe book, dated 1604, Hilary Spurling speaks indirectly to this question.4 She notes that Lady Fettiplace mostly avoids the violent purges, caustic poultices, and poison-filled tonic waters sometimes prescribed in the day in favor of gentle palliatives such as ointments, scent bags, soothing compresses, and stomach-settling drinks, many of which may well have been helpful. In fact, a great deal of early modern medicine was directed at increasing wellbeing rather than effecting cures. Perhaps this was simply inevitable given the lack of medical knowledge in the day, but there was also wisdom in this approach, wisdom that has been lost today. As Dr. Atul Gawande reflects in Being Mortal, doctors today too often prescribe, and patients too often accept, last-ditch treatments that are as excruciating as they are hopeless, as though mortality were a disease rather than a human condition.

Even though I know almost nothing about the complex subject of medical history, I keep up with The Recipes Project blog, for which Elaine writes frequently, because early modern medical recipes share certain features with the culinary recipes and sometimes provide insights into them. A particular area of overlap between early modern food and medicine was the humoral belief system, which (to greatly simplify) held that wellbeing was a matter of maintaining the four bodily humors in reasonable balance and that virtually all ingestible substances had properties that affected this balance in some specific way. Although faith in this system was on the wane in the early modern period, medical recipes were still framed by it, and thus medical recipes sometimes reveal humoral thinking in early modern cooking. For the most part, it seems that early modern people—and even medieval people—more often honored dietary rules than actually observed them in their cooking and eating. While a few dishes scream their humoral scrupulosity—like cold, moist sea creatures doused with hot, dry spices—most dishes, and nearly all surviving bills of fare, appear to ignore humoral precepts, if not flout them.

Violet syrup, used both for cure and for pleasure. Credit: annewheaton.co.uk

But there were exceptions. Certain items produced in the stillroom had originated as medicines and still retained medical uses in early modern England and yet had come also to be served as foods and drinks. Elizabeth Freke’s more pleasant cordial waters and syrups (assuming there were some) fell into this category. So did a number of other articles common in early modern English recipe books, such as candy-coated spices and nuts (comfits), spiced sugar candies, fruits and plant materials preserved in sugar syrups, fruit jellies, fruit conserves, quince pastes, marmalades, and crumb gingerbreads. These articles contained a variety of putatively beneficial substances and were purposed to alleviate diverse conditions. But their most important “active ingredient” was sugar, which was regarded in the humoral system as almost perfectly balanced and was, for this reason, a prime constituent of many humoral medicines. In sixteenth- and seventeenth-century England these sugary conceits appeared as foods primarily at banquets, glittering meals of sweets that the elite enjoyed both after great meals and as stand-alone entertainments. Banqueting was a delicious, often drunken, sometimes lascivious indulgence that was meant to flaunt the consumption of expensive sugar. But banqueting also had a curative subtext (or perhaps pretext) in that it supposedly facilitated the digestion, sweetened the breath, and revived the libido after heavy eating and drinking. Certain sugar-laden “banqueting stuffs” were still considered nutraceuticals into the nineteenth century. In 1829, American cookbook author Lydia Maria Child wrote that “economical people will seldom use preserves, except for sickness.”

Indian candied fennel seeds, which are comfits

The compilation of household recipe books in early modern England shifted the paradigm of knowledge generation. Earlier, knowledge had been largely generated by a few genius actors (often supported by wealthy patrons) and by political institutions, the church, and learning centers such as universities and medical schools. Knowledge generation was largely top down. With the advent of recipe books, knowledge was also generated in fairly ordinary households, both through collecting, testing, and writing recipes and through manufacturing products from recipes, during which new ingredients and methods were pioneered. This knowledge was widely disseminated through English society when manuscript recipes were taken up by printed books, a collateral development of the early modern age. Printed recipes, in turn, cycled back to manuscript, where they were further refined before once again returning to print. This cycling between manuscript and print was partly responsible for the speeding up of culinary fashions that occurred with early modernity. From 1200 to 1500, the cooking of the English elites changed hardly at all to judge from manuscript recipe collections. But starting in the sixteenth century, culinary styles were revamped every forty or fifty years, ushering in new ingredients and techniques and of course new dishes. Thus culinary knowledge rapidly increased, even if, then as now, older culinary knowledge tended to be forgotten, at least temporarily, every time tastes and fashions changed.

While the culinary recipes teem with clever, delicious new discoveries and beg to be cooked from even now, the medical recipes, I admit, generally strike me as backward-looking and blind with ignorance, not only useless but terribly sad. I will read a recipe for lemon cream followed by a hopeless medicine for “bleeding in the gut” and think what a shame that the people who ate such a lovely thing often suffered so terribly and died so young. But medical historians tell us that early modern cures were not actually as mired in the past as they appear to the uninformed—and that the same early modern recipe explosion that woke up cooking also spread and reinforced the habit of scientific thinking. In fact, many scientific discoveries about the human body and the natural world had already been made by the end of the seventeenth century. It is a pity that it took so long for these discoveries to bear fruit as effective medicines.

- Trudeau, Edward Livingston, An Autobiography (Garden City, New York: Doubleday, Page & Co., 1916). The book was republished into the 1940s and is available in several contemporary reprints.

- Commonplace Book of Elizabeth Freke, British Museum, Add MS 45718.

- In more modest homes that lacked a stillroom and stove room, women produced whatever medicines they could and bought the rest from physicians, apothecaries, and freelance purveyors like Hannah Woolley (1622-c.1675), who is better known as England’s first published female cookbook author. The use of commercial medicines and medical services increased among all social classes during the early modern period.

- Spurling, Hilary, Elinor Fettiplace’s Receipt Book (New York: Elizabeth Sifton Books, Viking, 1986), 18-20.