A few years ago, while reading the manuscript cookbook of the seventeenth-century English diarist John Evelyn,* I was surprised to come across a recipe called “To make Duch waffers”—or waffles. I had always been told that the English settlers of America knew nothing about waffles until they were introduced to them by Dutch settlers, and I had never questioned this story, for two reasons. First, the British do not eat waffles today, or at least they do not consider them a traditional British food. Second, there are no recipes for waffles in seventeenth -century English printed cookbooks, and I have seen only two recipes in eighteenth-century English cookbooks, and these recipes are easy to discount. Robert Smith offers what seems to be the first printed English recipe (as well as the first printed use of the word in English, says Wikipedia) in Court Cookery, published in 1725, but, goodness knows, anything might be fashionable at the Court. The other eighteenth-century English printed recipe of which I am aware is Elizabeth Raffald’s “Gofers,” in The Experienced English Housewife, published in 1769—if Raffald’s “Gofers” are, in fact, waffles. The peculiar word comes from the French gauffres, which can designate either wafers or waffles—the two are essentially thin and thick cousins—or some betwixt-and-between hybrid of the two, which is what Raffald’s “Gofers” appear to be. In any case, Raffald’s cookbook, like many other eighteenth-century English cookbooks, is filled with all sorts of obscure, pretentious French recipes that few of their readers had ever heard of, much less made. But Evelyn’s recipe turns out not to be an anomaly, for four of the six seventeenth- and eighteenth-century English manuscript cookbooks in the possession of the New York Academy of Medicine also have recipes for waffles. In three of these manuscripts, the word used in the recipe title is some cognate of “waffles.” In the fourth, the word is “gofers,” which actually designates two different recipes, one called simply “Gofers,” and the other “Dutch Gofers.” And what is the difference between them? So far as I can tell nothing. They appear both to be waffles. All of this strongly suggests that more than a few English were eating waffles from the late seventeenth century onward and that, therefore, waffles may have been popularized in America as much by English settlers as by the Dutch. This might partially explain why waffles were already so well known in colonial America that William Livingston, the aristocratic future governor of New Jersey, attended a “waffle frolic,” or waffle-centered supper party, in 1744. If American waffles were not so much a food fusion story as a fission story, they came here with a very big bang.

Five of the six waffles outlined in the NYAM manuscripts are, like Evelyn’s waffles, the usual seventeenth-century Dutch type. They are essentially buttery yeast-raised breads baked under pressure in a waffle iron, which makes them crusty and crunchy on the outside and tender and moist, almost custardy, within. In composition, they are the same as today’s “Belgian” waffles, but as made at the time, they may have looked and tasted somewhat different, as many of the old fireplace waffle irons had shallow grids and would have produced rather thin waffles with a high ratio of crust to crumb. But no matter what the iron, waffles of this kind are delicious, and so I have adapted the following recipe in the adapted recipes section of this site. The recipe comes from the 1791 manuscript cookbook of Elizabeth Duncumb, of the town of Sutton Coldfield, in Warwickshire.

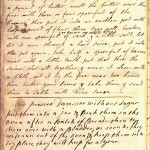

To make Wafles good Take half a pint of Cream & a quarter of a pound of butter, melt the butter over the fire with three or four spoonful of the Cream, then put it into an earthen pot with half a pound of flour, three Eggs well beaten with one spoonful of sack (or raisin or white Wine) & a little salt, let it run through a hair sieve, put it into the pot again, take half a spoonful of barm mixt with a little Milk, put that thro: the sieve, stir all together & cover it close with a Cloth, set it by the fire near two hours then butter your Irons & bake them & send them to Table with Wine Sauce—

One of the NYAM waffles recipes, from an anonymous late seventeenth-century English manuscript titled “Approved Receipts in Physic,” is an outlier. Its batter is essentially rice porridge stiffened with eggs. My good friend Dutch-American culinary historian Peter Rose is not aware of any Dutch precedent for this recipe, so it is quite possibly an English adaptation, perhaps inspired by the similar rice pancakes of the day, for which English cookbook author E. Smith published a recipe in 1727. A culinary historian is always interested in a local adaptation of an imported recipe, for it usually implies long familiarity with the original dish. When I made these waffles, I found it necessary to stiffen the batter with wheat flour in order for the batter not to run, and I suspect that flour was intended but was inadvertently omitted. In any event, if you would like to try these somewhat painstaking but delicious waffles, you will find my revised recipe in the adapted recipes section.

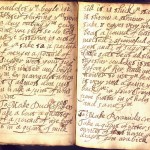

To Make Duch Waffers Take about a quarter of a pound of rise boyl it in a quart of milk till it is thick yn straine it throw a strainer yn take 8 egges very well beat a pound of butter melted 2 spoonefull of yest and 2 of sugger a little salt beat all these together and let it stand before ye fier halfe an hower to rise yn beat it very well againe yn bake ym in your Irons pore butter in ye holes and serve ym

According to Peter Rose, the seventeenth-century Dutch buttered their waffles hot and ate them with their fingers—both at festive meals and on the streets, where they were sold by vendors (which is interesting, of course, because it means that any English person visiting Holland would have seen waffles). In short, waffles, to the Dutch, were basically a sort of special bread. They were treats but hardly rarities: seventeenth-century Dutch paintings show waffles being enjoyed by common folk and gentlefolk alike. The seventeenth-century English, though, appear to have adapted waffles as what they called a “made dish,” a whimsical or fanciful dish, often of foreign extraction, generally served in the second course of dinner or supper and eaten with a fork and knife (or just a knife in households that did not use forks). The crucial clue is the sauce—melted butter enough to “pour” in the recipe directly above, but, in most other recipes, the day’s usual pudding sauce of butter, sugar, and wine, either “beat up thick,” as Evelyn suggests, or melted, as Elizabeth Duncumb seems to have in mind. The English serving conventions are important because they imply the kind of English households in which waffles were served: only the relatively well-to-do indulged in made dishes or dined and supped in courses.

If waffles, in England, were in fact a rather upper-class thing, it makes sense that we would find few recipes for waffles in early English printed cookbooks even if many (upper-class) English people ate them, at least on occasion. While English cookbook authors were generally all too pleased to print pretentious recipes, they would probably shy away from recipes that might strike their middle-class readers as simply ridiculous, as waffle recipes might if their middle-class readers did not own the specialized irons, which I think most did not. Fireplace waffle irons were essentially yard-long iron

tongs attached to thick iron plates; they were hinged either at the far end of the plates, like a nutcracker, or, less commonly, between the handles, like scissors. Waffle irons must have been fairly expensive in England, and a household would likely not invest in one unless it would be frequently used. And it probably would not be frequently used in most middle-class homes because waffles were a bit of a nuisance to bake. The heavy irons had to be propped just so before the fire and turned frequently and, obviously, they had to be watched closely. And according to Peter Rose, a single waffle takes six to eight minutes to bake in a fireplace iron, which means that producing enough waffles to fill a serving dish would take a half hour or more. In early nineteenth-century America, waffles were, in fact, a distinctly upper-class food, and while some privileged women did bake (or have their help bake) them at breakfast for family, they were mostly company fare. In addition to their continuing role in waffle frolics, parties, and suppers, waffles were considered among the nicest “warm cakes” to serve at a supper, or tea, to which company had been invited, and some hostesses also served them at dressier, more formal late-evening tea parties, though cookbook author Eliza Leslie objected, “lest the ladies’ gloves be injured with butter.” (Besides butter, most Americans of the day also sprinkled waffles with sugar and cinnamon.) In the mid-nineteenth century, when American women switched from cooking in the fireplace to cooking at stoves, waffles became somewhat less of a chore to produce, and they soon enough became a middle-class breakfast dish, often now served with maple syrup or molasses. Thus, Fannie Farmer organized her four waffle recipes, including one calling for cooked rice, in the “biscuits and breakfast cakes” chapter of her 1896 cookbook. Farmer’s waffles are all pleasant enough but not nearly as rich and delicious as their early English forebears. *Driver, Christopher, ed. John Evelyn, Cook: The Manuscript Receipt Book of John Evelyn. Blackawton, Totnes, Devon: Prospect Books, 1997.