WHAT MANUSCRIPT COOKBOOKS CAN TELL US THAT PRINTED COOKBOOKS DO NOT

Stephen Schmidt

Many of us who like to cook cannot resist the urge to save recipes, perhaps in a recipe box or a computer file or program—or, if we are not quite so organized, stuck to the refrigerator in ever-thickening sheaves that occasionally dislodge and flutter helter-skelter to the floor. From the sixteenth through the nineteenth centuries, many women (and a few men) of the English-speaking world also saved recipes, but they wrote them down in bound notebooks, often along with formulas for medicines, remedies, and household products like shoe blacking, brass cleaner, and ink. In the mid-1600s, as the word “receipt” (an etymological cousin to “recipe”) became the usual English term for a set of culinary instructions, these books came to be known as “receipt books.” Today these documents are typically referred to as “manuscript cookbooks” and are part of the collections of many American libraries, museums, historical sites, and other public institutions.

The Manuscript Cookbooks Survey concerns itself with English-language manuscript cookbooks begun by the end of the American Civil War, which are of particular relevance to researchers investigating what is often called “early American cooking.”[1] Not all of these cookbooks were authored by Americans. Many are English, some brought to this country early on by families of English descent and others acquired by institutions from book dealers. The English books are as interesting to students of early American cooking as their American counterparts, for American cookery began as a dialect of English cookery and was still pervaded by English influences through the antebellum period. This is discernible even by a non-specialist in recipes like mulligatawny soup, Welsh rarebit, bread sauce, plum pudding, and trifle, which run across the pages of American cookbooks, both manuscript and print, compiled as late as the 1860s.

To be sure, “early American cooking” was waning long before 1865 and lingered in traces long after, but the Civil War can nonetheless be taken as a watershed, for it accelerated various long-ongoing technological and material changes that underlay a mid-century revolution in American cooking. The most profound of these changes was the abandonment of fireplace (or hearth) cooking in favor of cooking at an enclosed wood- or coal-burning iron stove, a transition that was already well underway by the 1840s. Others included the modernization of American kitchens with respect to water supply, refrigeration, furnishings, lighting, and layout; the introduction of lightweight enameled cookware, mass-manufactured bakeware, and labor-saving devices such as the rotary egg beater; and the steady displacement of local and/or minimally processed foods by industrially produced foodstuffs that came to consumers in ready-to-use forms. These changes were accompanied by great social transformations such as urbanization, immigration, and the growth of the middle classes, which also played their part in revolutionizing cooking. Underlying all was America’s rapid industrialization. While it is not quite accurate to describe post-1865 American cooking as “industrial,” it was steered by ideologies of health, science, religion, and economy that arose in the context of industrialization and was therefore a much more modern thing than the cooking that preceded it. The cooking of Fannie Farmer, already foreshadowed in American cookbooks of the 1870s, looks somewhat familiar to us today, while the cooking of Eliza Leslie, the defining cookbook author of antebellum America, barely even seems “American” to us now.

A brief history of pre-1865 English-language cookbooks

It is often said that, historically, even the most privileged women had to worry over dinner, if only to decide the menu and give orders to their cooks. However, this seems not to have been true of the noble English ladies depicted dining at the privileged “high table” in medieval English illuminated manuscripts. If these ladies had had a hand in dinner planning, we would expect them to have compiled collections of their favorite recipes, as later home cooks did. But surviving medieval English recipe manuscripts, such as the famed Forme of Cury (circa 1390), are too detailed, too highly organized, and too comprehensive in scope to have been the work of even the most culinary-savvy noble ladies. It is more likely that these manuscripts were written (or dictated to scribes) by professional cooks in great households. Many of these manuscripts are penned on rolls and are cumbersome to read, so they were probably not even compiled as cookbooks but as records of the fabulous dishes royals and nobles could command.

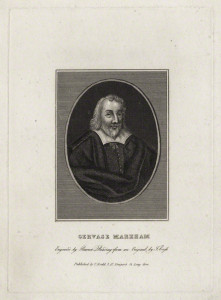

It was not until the mid-sixteenth century, late into the reign of Henry VIII, that English ladies began to keep recipe books, likely prompted by rapidly changing notions of dining. The elite no longer ate publicly in the great hall of the manor, staging a pageant of power, privilege, and largesse at the high table for an audience of manor dependents eating at lower tables before them. Instead, the elite now ate privately, in a specialized room that Gervase Markham, writing in 1613, called a “dining parlour,” transforming dinner into an intimate entertainment that revolved around sensual pleasure and social and intellectual stimulation. As good wives to their husbands and solicitous hostesses to their guests, English women now felt a responsibility to plan out the daily “bill of fare” and set their cooks to the task of preparing it. They could only do this if they had recipes.

The most privileged Tudor English ladies—those of the 120 (or so) families of the nobility and the wives of the greatest land-owning gentry and wealthiest wool merchants—had no difficulty collecting the latest and best recipes. They moved in circles with close connections to the court, the ultimate source of fashions, culinary and other. They had dealings with foreign dignitaries, high church officials, and celebrated cultural figures, all of whom might bear recipes. And they offered the pay and prestige necessary to attract the most experienced and highly skilled household cooks, most of whom, commented Tudor historian William Harrison (1587), were “musical-headed Frenchmen and strangers” (that is, foreigners, probably Italians and Spaniards), who brought with them a repertory of the “rare conceits” served at great feasts and the glittering little meals of sweets called banquets.

Slightly less privileged English women—the wives of small land-owning gentry, artisan entrepreneurs, and members of London’s professional and financial classes—had fewer opportunities to gather recipes. They did not have entrée to the charmed social strata in which the best recipes circulated, nor could they hope to snag a “professed cook” toting choice recipes from abroad. These persons were rapidly increasing in number and influence, for between the mid-sixteenth and mid-seventeenth centuries, England was among the most socially and economically fluid and upwardly mobile societies in Europe and a great deal of wealth flowed toward England’s upper-middling classes. And as the power and importance of the upper-middling swelled, so did their sense of self: they wanted to dine and entertain with the same splendor that their betters did. They needed recipes. English printers saw an opportunity: they would sell this group printed cookbooks.[2]

Of course, there were no cookbook authors in Tudor and early Stuart England, nor even a concept of such a profession. So printers turned to the manuscript cookbooks of elite English ladies, from which they cobbled together nearly all of the fourteen (or so) English cookbooks published before 1640.[3] Indeed, two early English cookbook “authors” explicitly acknowledged their indebtedness to ladies’ home manuscripts. John Partridge credited his 1573 book of culinary and medical recipes to “a certayne Gentlewoman (being my dere and special frende),” and Gervase Markham likewise recognized “an honorable [female] Personage of this kingdome” as the true writer of The English Housewife (1615), averring that he had only “digested the things of this booke in a good method, placing every thing of the same kinde together …” Markham’s sedulous attention to editing and organizing his book, which went on to become the best-selling English cookbook of the seventeenth century, was unusual. Most English cookbooks printed before 1640 are disordered hodgepodges, suggesting that they were lifted directly from ladies’ recipe notebooks.

By the mid-seventeenth century, English printers no longer had to pillage ladies’ receipt books for material. English interest in food and cooking was burgeoning, prompting a succession of chefs to the royalty and nobility—Joseph Cooper, the mysterious W. M., Robert May, and Patrick Lamb—to compose cookbooks, nearly all of which became bestsellers. In addition, printers brought out English editions of the cookbooks produced by the revolutionary new French chefs, La Varenne, Bonnefons, and Massialot, which likewise enjoyed enormous commercial success. Finally, there was the remarkable Hannah Woolley, active in the 1660s and 1670s. Woolley was not only England’s first published female cookbook author but also its first self-supporting woman of letters, a title she earned through her influential writings on female behavior (or etiquette) as well as through her five cookbooks. A lady’s maid in her youth and, later, a schoolmaster’s wife and self-taught maker of medicines, Woolley was mindful of the struggles of middling women, and she often broke her generally plummy address to speak explicitly to the needs of persons like herself. In her cookbooks she reworked recipes by tony cookbook authors like John Murrell and Robert May to make them feasible for those who had to worry about a budget and had limited kitchen help, and she provided bills of fare suitable to households of a range of incomes.

Woolley was the forerunner of a new breed of cookbook author that became increasingly typical over the course of the eighteenth century. These authors were women, and in ways both subtle and overt, they wrote as women, presenting themselves as having experience either as housewives or as professional female cooks. And, like Woolley, these authors strove to appeal to a broad audience comprising both highly privileged gentlewomen and women of the merely comfortable classes, a good commercial strategy as the latter group was steadily enlarging, as was their inclination to purchase cookbooks. It was from the ranks of these women writers that the most successful eighteenth-century English cookbook authors were drawn, above all Hannah Glasse, whose The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy (1747) was England’s canonical cookbook into the early nineteenth century and a primary source for many other cookbooks.

The relatively few eighteenth-century colonial American women who used printed cookbooks at all relied on European, mostly English, cookbook authors, and their favorites were the English ladies, including Hannah Glasse, whose book was imported into this country in great numbers and sat on the shelves of most of the founders of the American republic, and E. Smith and Susannah Carter, whose cookbooks were republished in American editions. It was not until 1796 that a plucky self-described “American orphan” named Amelia Simmons thought that American women might be ready for a cookbook of their own. She aptly titled her book American Cookery and proclaimed it “adapted to this country, and to all grades of life.” In truth, at least one third of the recipes that Simmons outlined in the first edition of her little book were lifted from English cookbook authors—and so were many of the recipes outlined by the antebellum American cookbook authors who followed Simmons, including Mary Randolph, Eliza Leslie, Mrs. Lee, Sarah Hale, Catharine Beecher, Sarah Rutledge, and Mary Cornelius. Indeed, English cookbooks remained popular in this country to the time of the Civil War, particularly Maria Rundell’s A New System of Domestic Economy (1806), which was republished in several American editions, and Eliza Acton’s Private Cooking for Modern Families (1845). Still, a more distinctively American style of cooking steadily stole upon the scene. Although Eliza Leslie triumphantly proclaimed her inaugural cookbook, Seventy-Five Receipts for Pastry, Cakes, and Sweetmeats (1828), “in every sense of the word, American,” half of the receipts (at least) could have fit comfortably in an English cookbook of the same period. Leslie’s book does not seem American to us today. But the 1859 edition of Mary Cornelius’s The Young Housekeeper’s Friend does.

The hundreds of English-language cookbooks published before 1865, particularly the more modern, more middling volumes that appeared in the two centuries separating Hannah Woolley and Mary Cornelius, provide the most complete and explicit account of early American cooking that we have. However, these cookbooks were not written to record the actual cooking of their time, any more than cookbooks today are, and a researcher cannot reconstruct a full picture of historical cooking and dining from them. Luckily, a researcher can consult other sources, including literature, painting, diaries, letters, and of course manuscript cookbooks, which English and American women produced in ever greater numbers even as the number and influence of printed cookbooks increased. One might assume—indeed, many people do assume—that manuscript cookbooks, because they were written solely for the practical benefit of their authors rather than to beguile potential book buyers, more closely approximate records of actual historical cooking than printed cookbooks. And some manuscript cookbooks, in some ways, do. But manuscript cookbooks, too, have limitations as historical documents, some of which they share with printed cookbooks and others of which are their own.

The elite perspective of both printed and manuscript cookbooks

People are often struck by the elite perspective of historical printed cookbooks: the richness, costliness, and complexity of the recipes, the fussiness of the serving conventions, and the implied elaborateness of the meals and entertainments in which the food was served. Manuscript cookbooks, contrary to what some believe, are similarly elite documents, for their authors were the same persons to whom the printed cookbooks were addressed. Historically, print was not the elite factor (although printed books were indeed expensive, especially prior to the nineteenth century). The elite factor was recipe use.

Historically, food was expensive, and so, more importantly, was the very activity of cooking. While not the insurmountable tasks that they may seem to us today, hearth cooking and brick oven baking were laborious, time-consuming, and tricky. And therefore sophisticated cooking—the kind that requires recipes—was impossible unless a household had, as antebellum American cookbook author Catharine Beecher put it, “the ordinary supply of domestics.” In middle-class antebellum households this meant a cook and an all-purpose housemaid. Wealthier households had more “help” than that. The proportion of Anglo-America that could afford the fine foods and household help essential to sophisticated cooking grew over time, to be sure, from a miniscule five percent (or so) in the seventeenth century to perhaps as much as a quarter of the (American) population by the time of the Civil War. And as the recipe-using segment enlarged, it also broadened, so that by the end of the eighteenth century, cookbooks purveying “frugal” cooking for the benefit of a less elite readership came to be published. Still, even these less elite works were written for a comparatively privileged audience. The fare outlined by Lydia Maria Child in The Frugal American Housewife (1829), addressed to “those not ashamed of economy,” looks downright Spartan to us today. And yet, as Child’s essay in the back of the book reveals, she assumed her readers employed a cook. Manuscript mirrored print. Some manuscript cookbooks written from the late eighteenth century onward clearly originated in households then considered middling, but the fare described in these books was far beyond the means of the majority.

This brings us to the subject of the household cook, whose presence is too often minimized or entirely ignored in accounts of historical cooking. In The Domestic Manners of the Americans (1832), Frances Trollope writes of that awful moment when she discovered that her cook was moonlighting as a prostitute and Trollope was forced to fire her on the spot–despite having “the dread of cooking my own dinner before my eyes.” Mind you, Trollope was not some super-privileged, high-born lady. She was a middle-class English woman who came to America with plans to open a dry goods store in Cincinnati. (Titled English ladies of Trollope’s generation barely knew where in their homes the kitchen was located.) To be sure, some women who employed cooks—such as Child’s middling readers—did considerable kitchen work themselves. And when expensive fruit preserves, complicated pastry, or rich cake needed to be made, even the most privileged English and American ladies were sometimes willing to pull on their aprons and get busy, trusting such delicacies to no touch but their own. Still, many women of the recipe-using classes personally “made,” with their own hands, few of the recipes in the printed cookbooks they owned and in the receipt books they wrote. They gave—or read—the recipes to their cooks, who may have dispatched them with the aid of still other hired help. This is not the way most of us today think of dinner happening and we therefore make misassumptions about the recipes of the past, particularly the very laborious or complicated ones, which we may be tempted to dismiss as mere wishful thinking because we can’t imagine ordinary housewives undertaking them. But these recipes did not belong to ordinary housewives.

Manuscript versus print

Some people come to manuscript cookbooks expecting to find a radically different cuisine from that seen in printed cookbooks of same era, perhaps on the assumption that cooking, historically, was created in home kitchens and was only recorded after the fact by cookbook authors. This may have been true enough during the early history of printed cookbooks, but by the mid-seventeenth century printed cookbooks had already become so widely used and so influential in elite Anglo-America that they created cooking as much as they recorded it. Dishes ricocheted from home cooks to cookbook authors, from manuscript to print, and then back again. Manuscript and printed cookbooks were part of a common process, both outlining more or less the same dishes and working in tandem to develop a shared cuisine.

This is not to say that manuscript never differs from print in specific points.

Some dishes do show up earlier in manuscript than in print. In the often-cited case of ice cream, which is recorded in English manuscript cookbooks going back to the Restoration but not in print until Mary Eales’s The Compleat Confectioner, published in 1718, there is an obvious explanation. Cookbook authors had surely eaten ice cream, for it was readily available at city confectioners’ shops, but they figured, correctly, that few women had access to the ice, the special equipment, and the cool place that were required to make it at home, and thus there was no point in providing a recipe for it. Other dishes that appear earlier in manuscript than in print—sweet potato pudding, modern trifle (with cake), “giam” (jam), and cooked meringue cake frosting come to mind—do not appear much earlier. Of course, any lag is interesting and begs further investigation.

Likewise, some dishes outlined in manuscript were never picked up in print or were printed only rarely. Most of these dishes were things that few people other than the manuscript writer and those in the writer’s immediate circle would have known: the specialties of local taverns, coffee houses, inns, hotels, or restaurants; dishes using unusual produce raised by the writer’s household; foreign dishes introduced to the writer through travel or by foreign-born acquaintances or family members; and dishes common only in the area in which the writer lived or among the social group to which the writer belonged. Most such outlier dishes turn out to be mere curiosities (if interesting ones), but some can alter one’s perception of significant matters. A case in point is the Dutch waffles outlined in a number of English manuscript cookbooks dating from the 1670s through the 1730s but, so far as I know, in only two printed English cookbooks of the era. Recipes for waffles would have been of interest only to the few worldly, unusually food-curious English who had taken the trouble to procure the special irons needed to bake them. This was evidently a subset too small to entice the attention of most period cookbook authors—but not too small to cast doubt on an important culinary story. It has generally been assumed that America learned of waffles directly from Dutch settlers of the Mid-Atlantic. Perhaps things were more complicated.

The most striking find in manuscript is the recipes themselves, their specific ingredients and method. Cookbook authors habitually copied each other, and so their recipes for favorite dishes tend to be similar, if not the same. Manuscript writers do sometimes copy or paraphrase recipes from cookbooks (some writers more than others), but, as a rule, their recipes are interestingly different from the usual print interpretations (and often nicer to contemporary taste, which is a happy thing for those staging historical dinners or adapting old recipes for a contemporary cookbook). Whether nicer or not, manuscript recipes are always useful, for they give us a broader sense of the ways in which people actually cooked the old dishes.

Collected versus accretive manuscript cookbooks

Most pre-1865 printed cookbooks outline a mix of bang-up-to-date recipes and tried-and-true classics, the former to entice fashion-aware, adventurous, and (perhaps) younger potential readers, the latter to assuage those who considered certain dishes proper or traditional for certain occasions. Culinary historians can spot the new dishes–they are the ones that do not show up in earlier cookbooks–but cannot readily discern if the older ones were truly current when the book was printed. Orange pudding, for example, appears in cookbooks published from the time of the English Restoration, in 1660, into the administration of President Andrew Jackson, in the 1830s, but was this pudding actually popular 100 or 150 years after it debuted? Or was this dish simply so drilled into tradition—so iconic—that cookbook authors dared not omit it, just as some general-purpose American cookbooks today dare not omit lobster Newburg, Boston brown bread, or apple pandowdy, even though few people today actually make such things? One might expect that manuscript cookbooks, as a rule, would focus more on currently fashionable dishes than on old-timey fare, but this is not always the case. It depends on how the specific cookbook was put together.

In her invaluable annotated edition of the so-called “Martha Washington Cookbook” Karen Hess makes a useful distinction between collected and accretive manuscript cookbooks. Collected cookbooks comprise the writer’s own collected recipes, which, for the most part, can be presumed to have been in their heyday during the writer’s lifetime, while accretive cookbooks consist largely of recipes copied from a book (or books) handed down in the writer’s family, to which the writer has added some recipes of her own. To be sure, many cookbooks straddle the fence, some collected books containing many handed-down family recipes (often in a clutch at the beginning of the notebook) and some accretive manuscripts so crammed (or back heavy) with newer-seeming recipes that they are nearly collected manuscripts. Still, it is never a waste of time to pay attention to the manner in which a manuscript was composed. If a researcher is trying to determine the fashionable dishes of a particular time—say, the decades leading up to the American Revolution—collected manuscript cookbooks will prove more useful. But accretive manuscripts tell a researcher something too: the persistence of certain dishes (more so in the past than now) across vast stretches of time, perhaps mostly in memory but sometimes on the table too, especially on nostalgic occasions like Christmas.

Unfortunately, it is impossible to tell how many manuscripts were composed, especially if they are written in multiple hands, as many are, or have various other complications too numerous to list here. Still, some manuscripts do bear clues. A cookbook whose recipes proceed in no particular order—a rabbit fricassee, followed by a cake, followed by a cough remedy—and whose (single) hand varies in mood, and whose squib is changing, was likely compiled over a span of time in the manner of a log or diary, which is say, it is likely collected.

Conversely, a cookbook whose recipes are organized (fricassees in one clutch, cakes in another), and which is written in a uniform hand (particularly if it is a fine one), with the same squib, was clearly copied. Alas, the question remains whether it is merely a fair copy, possibly of the writer’s own collected cookbook (see below), or whether it blends copied recipes with the writer’s own recipes, making it an accretive book. Ah, questions . . . they go on and on. In most cases, they can only be answered by intuition and context. But one particular type of accretive manuscript–one that was produced by some grand seventeenth-century English families (and not, it seems, by anyone else)–is readily identifiable. These cookbooks were recopied and updated across three or more generations, like successive editions of a printed book. In the course of copying, each new writer would move recipes added in the back of the book by the previous writer to appropriate slots in the body of the book, thus keeping the book both up-to-date and organized. Then, over the course of her kitchen career, the new writer would add recipes of her own in the back of the book, which would be folded into the body of the text when the book was next copied by her descendant. It is the recipes in the back of the book that provide the telltale clue that the cookbook is not merely a fair copy but an accretive cookbook. Karen Hess pegs the “Martha Washington Cookbook” as an English accretive manuscript of this kind. Last copied around the time of the Restoration, in 1660, the manuscript was passed on to Martha Dandridge, by means unknown, on the occasion of her first marriage, to Daniel Parke Custis, in 1749. By this point, the recipes in the book, some dating back to Tudor days, were mostly archaic and it is unlikely that Martha Washington ever used any of them.

Many neatly copied manuscripts were copied not from a handed-down cookbook but from the writer’s own recipe collection, which the writer may have kept in a notebook or perhaps on loose sheets stuffed in a desk drawer. Some writers make a stab of organizing their recipes in the course of copying them, but not all. The Restoration-era English manuscript titled Choise Receipts, in the collection of the New York Academy of Medicine, was almost certainly copied directly from the author’s original receipt book, for the recipes proceed higgledy-piggledy and two failed recipes for the same cake appear in the book’s midsection, followed by a third successful recipe that concludes with the triumphant line, penned in large bold characters: “The receipt is approved of.” The lack of editing seems odd, for Choise Receipts is a grand production: it is gorgeously penned, obviously by a professional scribe, in an enormous leather-bound folio volume with an engraved brass clasp. My theory is that its author was a member of England’s Royal Society, who, in the spirit of science, was aiming to record his actual culinary journey, and thus organizing the recipes (and deleting failed cake recipes) would have undercut its purpose.

The nineteenth-century American Hoffman family manuscript cookbook, also in the collection of the New York Academy of Medicine, is likewise unmistakably a fair copy of the recipes collected by the writer. But unlike Choise Receipts, the Hoffman cookbook is organized and its point was very much to be a working cookbook, not a library record. Written in halting English by a German immigrant to America, the recipes comprise a mix of typical German dishes (similar to those we associate today with the cooking of the “Pennsylvania Dutch”) and classic American fare like roast turkey and pumpkin pie. The recipes are atypical both in their homey simplicity—manuscript cookbooks tend to focus on more complex cooking—and in their painstakingly detailed explanations, as though the writer is speaking to someone other than herself. And it turns out that she is. After hyperbolically praising a recipe for ersatz coffee made from dried apple slices, extolling the beverage as “better coffy then of all store coffy no dought its wholesomar two try it,” the writer addresses those who might someday have no choice but to resort to it: “My dear little motherless grand grand children,” she writes, “its well enough to know [those?] things—we don’t know what is before us in the world we may become poor or […?].” Evidently the writer’s great-grandchildren had lost their mother, and the writer was stepping in to give them recipes that their mother did not have a chance to pass on.

Idealized versus actual cooking

Some years back I attended a talk on early eighteenth century American foodways given by a university professor and noted culinary historian. Granted, his focus was “the common folk,” but nonetheless I was dumbstruck when he off-handedly acknowledged that he had never looked at any British cookbooks of the period, despite the fact that, in the run-up to the Revolution, several bestselling British cookbooks were imported into this country in substantial numbers and two were published in American editions. His assumption, which I’ve since learned is shared by many others, was that historical printed cookbooks purveyed idealized cookery, eliding the simple (and boring) fare that people actually ate from day to day and instead harping on fancy (and fun-to-read) company dishes, particularly the most expensive, most elaborate, and trendiest ones that were likely the least often broached. In short, historical cookbooks were mostly fantasy conjured by their authors to sell books. Are the printed cookbooks guilty as charged? And are manuscript cookbooks useful correctives?

It is indeed difficult to extract a sense of daily cooking from printed cookbooks, but not because simple recipes are lacking. Most historical printed cookbooks aimed to be all-purpose, comprehensive volumes (like today’s Joy of Cooking) and therefore outlined all sorts of extremely simple dishes, like meat broth, roasted meat, scrambled eggs, boiled vegetables of all sorts, fried potatoes, porridge, and even toast. The problem for the culinary historian is that the cookbooks cannot be counted on to indicate which of these simple recipes were also inexpensive, easily provisioned, and easily executed (given the material and technological conditions of the day) and thus, presumably, in common daily rotation. Cookbooks do become somewhat more helpful on this matter as time goes on. Hannah Glasse, for example, marks certain dishes “cheap” or “plain” in her cookbook of 1747, and nineteenth-century cookbook authors add the terms “common” or “family.” Some nineteenth-century authors also lay out family dinner menus. In her cookbook of 1847, Eliza Leslie even provides different sets of family menus for “very plain” and “nice” dinners. Still, even in the later cookbooks, the simple recipes whose use goes unmentioned for exceed those that are slotted into everyday meal plans. Perhaps this is to be expected. People knew which dishes were feasible for family, just as we do.

It would be lovely if manuscript could tell us what print fails to on the matter of daily cooking, but, for the most part, manuscript is not helpful. Contrary to what many expect, manuscript writers (with some exceptions) collected few recipes for simple dishes. After all, they had cooks who already knew how to make such things. And if their cooks happened not to know, they could always consult a printed cookbook. The only simple dishes that are common in manuscript are those that were understood to require formulas rather than being simply a matter of experience and knack. Among these dishes were the plain puddings often brought out with or before the principal meats at dinner and, in antebellum American receipt books, the “warm cakes” that were served both at breakfast and the usual evening meal (often referred to as “tea”): muffins, shortcakes, biscuits, corn cakes (cornbreads), griddle cakes, and waffles—as well as doughnuts, crullers, and rusks, which were commonly considered part of the group although served cold. In addition, women recorded many recipes for preserved foods—pickles, collars, souses, and potted dishes—likely because preserving involved clever little tricks that were easily forgotten but that could make a big difference for better or, literally, for ill.

While print tends to bury its daily fare, it shouts its company cooking from the rooftops. Historical printed cookbooks are stuffed with fine dishes, and there is no missing the finer among them: their cost, richness, complexity, and labor-intensiveness often shock. And while it is no doubt true, as alleged, that many of these elaborate dishes were cookbook author fantasies, little known and rarely made in their time (just like many of the fanciful concoctions in today’s cookbooks), it is possible to zero in on the actual period favorites. Dishes that show up in most or all of the printed cookbooks of a given era were almost certainly popular, as were dishes that are listed in multiple cookbook bills of fare. To be sure, some cookbook bills of fare are themselves clearly flights of fancy. Who other than perhaps King George III served a January dinner consisting of three courses of twenty-five dishes each, as laid out by Elizabeth Raffald in her bestselling cookbook of 1769? But most cookbook bills of fare jibe in a general way (in the numbers and types of dishes served and in the arrangement of courses) with surviving actual bills of fare, of which a surprising number are extant. A fabulous source is the household account book of Lady Grisell Baillie, an extremely wealthy English noblewoman of the late-Stuart and early-Georgian era who apparently rushed back to her palace (still standing) after every dinner party and wrote down what was served. The book has been published. [5]

Manuscript writers, who were particularly, and sometimes exclusively, interested in company cooking, tend to confirm the company scene implied by print authors. The company dishes most often recorded by manuscript writers are the same ones featured most prominently by contemporaneous cookbook authors, both as recipes and as suggested items in their bills of fare: chicken fricassees, calves’ heads productions, and Scotch collops (scored veal scallops) in the seventeenth century; beef a la mode, roasted tongues and udders, and morels in cream in the eighteenth; soups of all sorts, roasted ham and turkey, and macaroni with butter and cheese in the nineteenth. To be sure, manuscript writers do sometimes show favor to certain dishes that print authors scant. I am thinking here in particular of a dish called shoulder of mutton roasted in its own blood, which for some reason (perhaps its weirdness) has always gripped my imagination. A recipe for this dish is outlined in The Compleat Cook (1655) but in only one other printed cookbook I have happened upon and not in any printed menu that I recall. Therefore, I had long doubted that anyone actually made (or even seriously contemplated making) this odd specialty. But the manuscript cookbooks suggest otherwise. The Compleat recipe is copied verbatim in Choise Receipts and versions of the dish show up in three other Restoration-era manuscript receipt books that I have looked at. Jean Gemel, whose cookbook is at the New York Academy of Medicine, outlines an unusual (and elaborate) variation, possibly of the author’s devising, that entails boning the bloody shoulder, rolling it up with minced suet and spices, and pressing it under a weight for three days before roasting, whereupon, the author promises, the mutton will taste like venison. As a rule, only popular (and perhaps shopworn) recipes are subjected such imaginative fiddling.

Unsurprisingly, the (lamentably few) company bills of fare jotted down by manuscript writers—most of which describe meals that were actually served to or by the writers and so are especially interesting—mirror the cookbook bills of fare. Still, there are some fascinating discrepancies. For example, the 1682 receipt book of Joan Yate, part of the superb Whitney Cookery Collection, housed at the New York Public Library, implies a convention that, while perfectly logical (at least to us moderns), goes unrecorded in late-Stuart printed English cookbooks. When Joan Yate staged an ordinary company dinner, she presented it as was customary at the time: in two courses, the second of which mixed savory dishes and sweet. (Diners could choose one or the other, or they could choose to sample the savory dishes and then the sweet, in which case they would ask a waiter for a change of plate.) But when Joan Yate served a deluxe company dinner, she presented it in three courses and made the entire second course savory and the third sweet, so that the third course became a dessert. That Mrs. Yate, in her book, explicitly refers to the third course as “dessert,” a new term borrowed from the French, is itself of note: the major print cookbook authors of her era, including Robert May and Hannah Woolley, still call a course of sweets by its original English name, a “banquet.”

Finally, in one aspect of the company repertory manuscript does differ markedly from print. Manuscript has fewer recipes for the extremely complex dishes for formal entertainments, such as turtle soup (which requires complicated, gory butchering), sculptural raised meat pies filled with twenty different morsels, and calves’ heads that are partly roasted, partly hashed, and partly fricasseed. Also largely absent from manuscript are the more highfalutin French dishes—the puptons (terrines of sort), epigram dishes (elaborate stews), and cullises (laborious, complicated reductions used as sauce bases)—introduced by a steady stream of translated French cookbooks published starting in the 1650s and picked up by many English cookbook authors. (American cookbook authors showed only tepid interest in fancy French cooking before the Civil War.) It is probably true that these dishes were not often made, but I don’t think their near absence from manuscript necessarily indicates that they were hardly made at all. Rather, I am inclined to think that women did not usually trade such recipes among themselves, for the very reason that they were so complex, but instead sought the recipes in their printed cookbooks. We would likely do the same today, perhaps begging the recipe for a friend’s luscious macaroni and cheese—but probably not for his or her show-stopping Indonesian rice table. For that we would go to a cookbook.

Sweet dishes and cakes

It will surprise (and perhaps disappoint) many who are new to the study of English-language manuscript cookbooks that the principal dishes of the meal as we now think of them—that is, preparations of meat, fish, vegetables, and the like—seem not to have been the main interest of manuscript writers. The majority of manuscript recipes concern sweet cookery, which, historically, was conceptualized in three broad categories: preserves and sweet wines (both typically made with fruit); sweet dishes or “desserts” (usually grouped as puddings,[6] pastry, and the so-called custards, creams, and jellies); and sweet cakes, both large (like pound cake) and “little” (cookies in modern terms). An especially avid collector of sweet recipes was

Emma Embury, a respected nineteenth-century American poet and writer, whose manuscript cookbook is in the collection of the New York Public Library. Embury recorded over eighty recipes for sweet cakes and warm cakes, about fifty recipes for pies and puddings—and just twenty-two recipes for meats, fish, vegetables, sauces, condiments, and other savory preparations, all of which she corralled under the unprepossessing heading “miscellaneous.” If Embury’s selection of cakes and warm cakes is a little outsize even for the period, there is a likely explanation. Antebellum American company entertainments were often staged as teas of some sort (and there were many sorts), for which cakes of all kinds, both sweet and warm, were wanted. Embury hosted a famous salon in her New York City home in the 1830s, and the refreshments at her salon were likely organized as teas.

One reason that sweet recipes occupy so much space in receipt books was that, like the warm cakes, these conceits required recipes—exact formulas.[7] But, more importantly, sweet cookery was deeply rooted in Anglo-American culture. The English were already notorious in Europe for their love of sugar by the sixteenth century—they even stirred sugar into wine, to the horrified amazement of foreign visitors—and by the eighteenth century the English were the world’s leading per capita sugar consumers, outflanking the French by a factor of ten by 1789. The American colonists picked up the sugar habit early and were able to indulge it, for they could buy sugar relatively cheap due to their proximity to England’s West India sugar colonies. Over the course of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the repertory of Anglo-American preserves, sweet dishes, and cakes grew ever larger and more sophisticated and sweet cookery became ever more central to Anglo-American meals and entertainments. Meanwhile, the price of sugar (as well as refined wheat flour) steadily dropped, permitting an ever broader segment of Anglo-America to participate in sugar culture and diverting the interests of home cooks on both sides of the Atlantic disproportionately toward preserving, dessert-making, and cake baking. Surveying American home cooking in the mid-nineteenth century, Catharine Beecher lamented that American women could whip up a perfect cake or sparkling gelatin jelly yet could not produce a decent lamb chop or baked potato.

To a degree, the preponderance of sweet cookery in manuscript mirrors a similar imbalance in print. Early English cookbooks are brimming with sweets, or “banqueting stuff”—indeed, most of the English cookbooks published during the first half of the seventeenth century are essentially banqueting books—and eighteenth-century English cookbooks are freighted with fancy new puddings for dinner and fancy new cakes for evening tea parties. American cookbooks followed the same pattern. The first edition of Amelia Simmons’s American Cookery (1796) is almost entirely given over to sweet dishes, cakes, and fruit preserves (the second edition is somewhat less skewed toward sweet), and America’s first best-selling cookbook was Eliza Leslie’s Seventy-Five Receipts for Pastry, Cakes, and Sweetmeats (1827), which we would today call a dessert cookbook. Still, English-language printed cookbooks are not nearly as sweet-focused as the manuscript cookbooks. Whether the receipt books are giving us a truer account of how women (or their cooks) actually spent their time in the kitchen or whether they merely tell us which recipes women most enjoyed collecting is hard to say.

Because they are so focused on desserts and cakes, American manuscript cookbooks bring into relief period tastes and trends in sweet cookery that might not be noticed in the print record. A case in point is sweet potato pudding. Antebellum printed cookbooks of the Mid-Atlantic and New England outline a fair number of sweet potato puddings, many of which are baked in pastry crusts and were, as served in most households, basically sweet potato pies. Contemporary readers might be tempted to discount these recipes as anomalies because we now think of sweet potato pie as a peculiarly southern specialty. But antebellum manuscript cookbooks confirm that the pudding was also a Yankee favorite, for most have recipes. Indeed, one of the New York Carew family cookbooks, in the collection of the New York Public Library, outlines seven potato puddings (some white, not sweet) in a row.

Even more surprising is the manuscript account of America’s early use of chemical leavening. Food writers today almost unanimously assert that chemical leavening—that is, baking soda and baking powder—were embraced as wondrous advances in cake-baking when introduced to American kitchens starting in the late eighteenth century. The printed cookbook authors of the period, however, tell a different story, particularly Eliza Leslie, the best-selling and most influential American cookbook author of the second quarter of the nineteenth century. While Leslie grudgingly accepted the use of chemical leavenings in the “plain” cakes served to family, she abhorred and absolutely forbade the introduction of these substances into the “fine” cakes served at elegant evening parties. Was Leslie speaking for a broad segment of antebellum American women, or was she, as another cookbook author of her time implied, an out-of-touch purveyor of ruinously expensive, laborious “rich cooking”? The writer of the Hoppin family manuscript cookbook (circa 1840), which is in the possession of the New York Public Library, leads us to surmise that Leslie was indeed speaking for many others, for the Hoppin writer pointedly eschews both pearl ash and saleratus, the two common “baking sodas” of the time, in all of her nice cakes. In her recipe for Queen Cake, the Hoppin author writes “no saleratus,” while in a recipe for “very rich cake,” which she got from her friend Nancy Sweeting and marked “excellent,” she notes, “pearl ash or not, better without.” And in a long, rambling paragraph detailing what seems to have been a fairly desperate struggle to find “the best way to make delicate cake in loaves” she decrees “no saleratus,” and underlines “no” with a thick, bold stroke. The writer outlines six additional recipes for fine cake, and in not one does she call for chemical enhancement.

Vague recipes versus concrete recipes

A maddening shortcoming of historical printed cookbooks is the pervasive vagueness of their recipes, which often fail to indicate precise quantities of ingredients, proper seasoning, desired consistency, the shape, size, or number of the thing, the pot or pan required, the strength and duration of the heat, and ever so much more. There are many seventeenth-century print recipes for venison pasty—and many seventeenth-century references to the dish in bills of fare and elsewhere—but none of these recipes is sufficiently explicit to permit us to reproduce some fair facsimile of this once-beloved dish today. Hannah Woolley tells us to make the pastry dough with fourteen pounds of flour, three pounds of butter, an egg, and as much cream “as you think fit,” and then to roll it out “pretty thin and broad, almost square” and lay “some butter” and an unspecified cut of venison on top. This is all helpful, but, alas, her forming instructions skip from here to “close it up and bake it well, but you must trim it up with several Fancies made in the same Paste.” Good luck to anyone attempting to produce a venison pasty that a seventeenth-century person might have recognized.

One reason that Woolley felt free to omit so many details is that she assumed her readers already knew how a conventional venison pasty was constructed and what it was supposed to look like when finished. We make similar assumptions today when writing recipes for common dishes like hamburgers, lasagna, and brownies. And three hundred years hence, when these dishes will have disappeared, along with the buns, the pasta noodles, and perhaps even the chocolate with which they are made, our recipes may make as little sense to our descendants as Woolley’s venison pasty recipe makes to us. The vagueness of historical printed recipes—as well as their occasional inconsistencies, contradictions, or outright nonsensicalness—can also be laid to manner in which the recipes came to be. Historically, cookbook authors copied most of their recipes from other cookbook authors and never tried the recipes in their own kitchens. Thus they did not always catch omissions and errors, and even when they did, they did not always understand the recipe well enough to fix it. Everybody knew that this was the way printed recipes happened and no one thought much about it, unless a cookbook author extracted such spectacular success from other people’s work that she could not help incite comment. This was the case with Hannah Glasse, author of the bestselling The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy (1747). “She steals from everyone,” fumed one of her envious rivals.[8]

Unfortunately, manuscript recipes are often no clearer or more complete than those in print. Many manuscript recipes were jotted down in haste and are mere strings of ingredients. Furthermore, most manuscript writers tried only a smattering of the recipes that they copied into their notebooks, just as many of us today have tried few of the recipes in our recipe boxes, desk drawers, or computers. And even when writers did try a recipe—when they explicitly indicated as much by marking a recipe “good” or “made” (or implicitly, by crossing it out)—they rarely wrote down what they did or why they did or did not like the result.

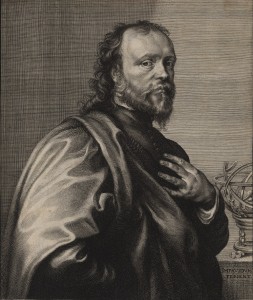

However, there were exceptions, such as certain early members of England’s famed Royal Society. The society was founded shortly after the 1660 Restoration of the English monarchy, which brought an end to the drab, pettifogging rule of the Puritan Interregnum and ushered in a new era that celebrated the pursuit of luxury and pleasure, including the luxuries and pleasures of the table. All of the English elites were in the thrall of the new Epicureanism, as the English then called gourmandise, but interest ran particularly high among society members. As scientists, these men were not only captivated by the sensual pleasures of eating but also fascinated by cooking as a branch of natural knowledge. They were drawn to collect recipes by the same instinctive curiosity that led them to collect seashells or rock specimens, and they tested recipes in the same way they would any scientific formula, experimenting with them under controlled conditions and carefully recording both the process and the results.

It seems likely that many society members kept cookbooks, for many Restoration-era English receipt books in library collections bear suggestive traces of society authorship. However, only one such cookbook was published in the day, that of international celebrity-rake Sir Kenelm Digby, which was shepherded into print by his assistant in 1669, shortly after the author’s death, and went on to become a bestseller. Digby collected literally dozens of recipes for the alcoholic libation called metheglin, some of which run on for pages, and if you really want to make this brew, there is no better place to look. Sugar cakes (essentially butter cookies) are outlined in several early English printed cookbooks, but only Digby tells us what these little cakes—or at least those common in his particular bailiwick—looked like: “about the bigness of a hand-breadth and thin.” A careful recipe writer today would express the width and depth in inches, but let’s not quibble. Like many manuscript writers, Digby came by many of his receipts via friends in the aristocracy, and his pal Lady Lasson provided a gem. Her crust for mince pies, exclaimed Digby, was made in the new way, with cold butter and cold water, not hot, and thus it was marvelously “short and light” rather than plaster-hard like the hot-dough crusts of the past. How wonderful to have a first-hand account of the seventeenth-century English pastry revolution, an event that we can infer from printed cookbooks but not experience.

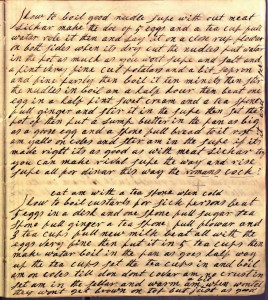

The receipt book of Royal Society founder and famed diarist John Evelyn, which was published only recently, is messy and sometimes challenging to read, but it is broader in scope than Digby’s book and even more bursting with concrete, specific detail: the proper way to construct a cheese vat from straw; where in the chimney to hang sausages for smoking; the precise way to overlap apple slices for a tart; and—humorously—a warning not to eat your sack posset too hot, “lest you scald your chops.” (The posset recipe, a gift of Lady Cotton, is a marvel on several counts.) As a dessert researcher, I am particularly grateful to Evelyn for his scrupulous recipe for Portugal cakes, the earliest modern English butter cake, the direct ancestor of pound cake, and the ultimate sire of all modern American butter cakes, whether white, yellow, chocolate, or red velvet. Printed cookbooks indicate that Portugal cakes were baked in smallish individual molds, but just how small the cookbooks do not say. Evelyn does: his recipe requires twenty-four pans. Now, if only Evelyn had also told us whether these pans were pattypans (akin to tartlet molds) or something else . . . but, again, let’s not quibble.

Living some two hundred years after Digby and Evelyn, and an ocean away, the writer of the Hoppin family receipt book (whose aversion to chemical leavening is noted above) was another uncommonly thoughtful and observant cook who bequeathed a wealth of information to us not available in print. Scups, she notes, are “a cheap kind of fish to make common chowder such as made at fishing parties if other fish is not to be had such as blackfish,” alerting us to the use of a fish that printed cookbooks rarely mention and giving as an insight into an entertainment that we barely knew existed. Another lovely find is her recipe for gravy browning, a concoction largely absent from the print record. Hers is a solution of water and burnt sugar—that is, really burnt, “until it becomes bitter and black.” “It will sometimes sour in hot weather,” she cautions, and so one must “make it often or keep it in a cold place.” Among the most puzzling recipes in old printed cookbooks are those for wedding fruitcakes, which invariably call for huge quantities of ingredients—three pounds each flour, sugar, butter, and eggs and ten pounds of fruit are typical—but never tell us the number and size of the pans in which this enormous batter was baked. The Hoppin writer does, and what she writes shocks us: her wedding cake is baked in multiple small round pans holding only one quart. Perhaps waiters passed these cakes to wedding guests “sliced but the slices not taken apart,” as Eliza Leslie, in a cookbook dating from the same decade as the Hoppin receipt book,[9] says was proper for an evening tea party. This is certainly not how we today picture wedding cake.

Like many other receipt book writers, the Hoppin writer particularly focuses on desserts, about which she has much of interest to say. Struggling with rennet, a solution of dried calf’s stomach used to clabber milk into rennet custard (and also to make fresh cheese for cheesecakes), she wonders on the page if brandy might “give a better taste than wine,” the usual vehicle. If the Hoppin writer ever followed up on this idea, she may have used the “white brandy” called for in old recipes for brandied peaches, to our mystification. Evidently, it was Pisco, for the Hoppin writer comments that it came from Peru. Sugar gingerbread should be decoratively stamped with a carved mahogany mold, as for Christmas cookies, she remarks—which does not really surprise us, as molasses gingerbread was often decoratively stamped. Yet we did not know this, as the convention goes unmentioned in printed cookbooks. How do we prevent the crusts of apple pudding pies from going soggy? Of course: we need to drain the apples after grating if they are especially juicy—and we also need to step up the sugar if they are extra sour. And why do we have a sense that antebellum pies were smaller than those we know today? Because they were smaller, or at least the Hoppin writer’s pies were: she could make crusts for nine covered pies from one pound and a half of flour and one pound of butter, while we could only eke out three contemporary standard 9-inch covered pies from the same ingredients.

Finally, under the heading “To Be Remembered,” dated 1838, the Hoppin writer describes in astonishing detail a successful dessert that she served to company—so that she could remember how to serve it again. Consisting of two stirred (or saucepan) custards, a bright-yellow one made with only the yolks of eggs, and a pure white custard made with only the whites, the dessert draws on a hyper-fashionable cake trope of the time, which involved serving cut squares of white and yellow cake together, either jumbled in a cake basket or stacked alternately into an imposing pyramid on a plate. So far as I know, no antebellum American printed cookbook makes reference to a dessert similar to the Hoppin writer’s—or, for that matter, gives a recipe for precisely the sort of egg-white custard that I suspect she made. Quite possibly the idea was the Hoppin writer’s own. In any event, for those of us beset with an odd compulsion to recreate period desserts, this passage is a magical find.

When having company to dinner, as when the Whitneys were here for a dessert, make Lemmon Custards of the yolks of eggs, making them yellow, and take the whites of the Lemmon receipt with one or two more eggs for white boiled Custard seasoned with mace and orange peel pounded very fine and sifted so as not to speck them, and add a little cream. This is the answer instead of whips in the summer or any time. Put the custards into the low jelly glasses & serve them on the dinner table on the china custard stands, one white & one yellow, to look very handsome, or sometimes put the white custards in glass handle cups and set the yellow & white on the glass stand.

[1] American institutions also possess pre-1865 English-language manuscript cookbooks originating in Scotland, Ireland, Canada, and elsewhere, and the Manuscript Cookbooks Survey includes these books in its database.

[2] The super-elite bought printed cookbooks too, to be sure, as is evident from the many recipes from these books that they copied into their home receipt books.

[3] The exceptions were two Elizabethan volumes translated from published Italian works and the cookbooks of Jacobean author John Murrell, who appears to have been a working chef and whose recipes bid fair to have been his own.

[4] Print cookbook authors did try to do this, and some succeeded. See, for example, Mrs. Lee’s disquisition on melted butter (which, it should be noted, she copied from an English cookbook author) in The Cook’s Own Book (1832) or Lettice Bryan’s (apologetic) manifesto on toast in The Kentucky Housewife (1839).

[5] The Household Book of Lady Grisell Baillie 1692-1733, edited, with notes and introduction, by Robert Scott-Moncrieff, W.S. (Edinburgh: printed at the University Press by T. and A. Constable for the Scottish History Society, 1911), digitized by the Internet Archive in 2008 with funding from Microsoft Corporation

[6] The place of puddings in the Anglo-American dinner changed over time. Through the middle of the eighteenth century, puddings were typically served in the first course of dinner, as accompaniments to the boiled and/or roasted meats, and were not classified as sweets of any sort. During the second half of the eighteenth century, puddings gradually transitioned to the second course of dinner, and by the nineteenth century most were considered desserts, at least in America. (In England, the early nineteenth century serving conventions for puddings were more complicated.)

[7] Precise recipes for preserves, sweet dishes, cakes, and some breads, with weights or measures given for all ingredients, had already begun to find a place in both manuscript and printed cookbooks by 1600 and were common by 1650. In contrast, precise recipes for savory dishes only began to appear in the eighteenth century and were not the rule until the end of nineteenth century.

[8] The famed dictionary writer Samuel Johnson was more blasé. Of course Glasse had plagiarized, said he, for “such a work is chiefly done by transcription.” And therefore, Johnson went on to boast, he, a master of all things editorial, could write a better cookbook than anyone! In truth, Mrs. Glasse had tried, or at least rethought, many of the recipes that she was accused of having stolen, for she often reworded crucial passages or added material.

[9] The Lady’s Receipt-Book, Philadelphia: Carey and Hart, 1847, page 391.