By Stephen Schmidt

The library of Harewood House, Yorkshire, UK. Mrs. Flint staged her November 1862 in her home library, which may have been similar.

Those who have read my post about Catharine Dean Flint’s evening parties and late-night suppers know that Mrs. Flint was an ideal hostess—someone who knew the latest fashions and whose entertainments were certainly stylish, but also someone who was secure in her sense that she knew best how to please her particular guests and so was not afraid to do things her own way. Mrs. Flint also had the perfect temperament for a hostess (and perhaps for anyone). When something went awry at one of her parties—when the silver arrangement was a tad too crowded, or the dessert display was awkward, or too many plates of scalloped oysters went uneaten—she did not let herself get upset. Instead, she wrote down what had gone wrong in a notebook so that she would know how to better manage things the next time.

Now in the possession of the American Antiquarian Society, in Worcester, Massachusetts, Mrs. Flint’s notebook tells us that she once again marshalled her formidable skills as a hostess—and displayed her equable hostess temperament—on the evening of November 7, 1862, when she staged a formal dinner for eleven people in the library of her fine Boston home. Sixty years old at the time of this event, Mrs. Flint had been schooled in a style of dinner-giving called service à la française but had lived to see a new style, called service à la russe, come into fashion. Mrs. Flint neither slavishly clung to the old way nor heedlessly embraced the new but instead merged the two styles, delightfully, into service à la Flint. As it turned out, there was a glitch in her November 1862 dinner, but, as usual, Mrs. Flint took it in her stride.

Second course by Elizabeth Raffald, 1769, with serving dishes specially shaped for specific table positions.

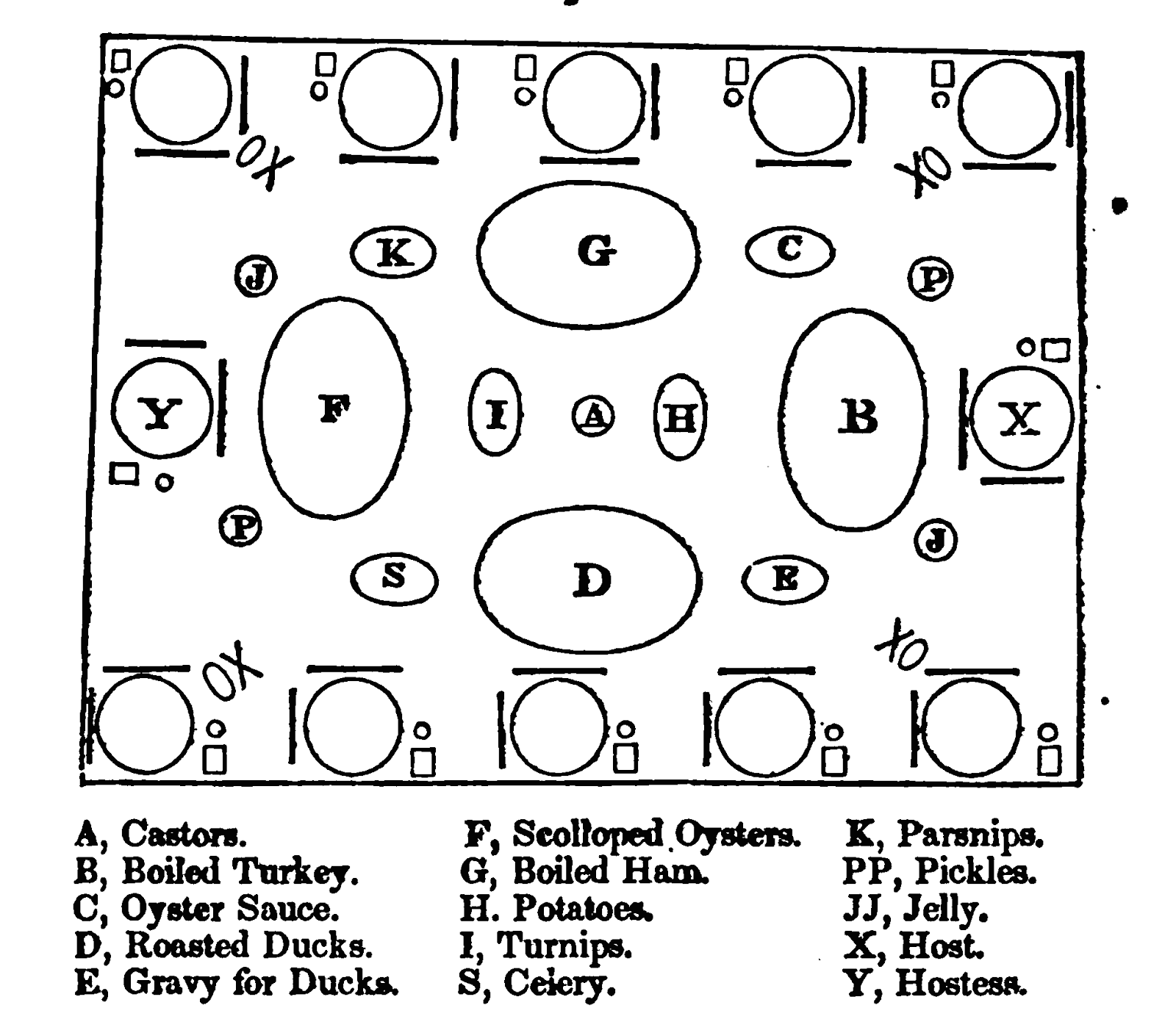

From the mid-sixteenth to the mid-nineteenth centuries the Anglo-American formal dinner was served à la française, or French style. The antebellum American version of service à la française (which differed from the contemporaneous British version) entailed two principal courses, the first savory and the second sweet, plus a little caboose course called dessert. In her cookbook of 1846 Catharine Beecher lays out a typical French-style menu “for what would be called . . . in the most respectable society . . . a plain, substantial dinner.” Her first course comprises a soup, a fish dish, two principal meats (a turkey and a ham, a common choice), a game roast (ducks), a fancy side dish (scalloped oysters), several plain vegetables, and various sauces and condiments. By Beecher’s day, the first course had become, de facto, two courses, as the soup and the fish were brought to the table and served first—most diners ate one or the other, not both—before the rest of the course was laid on.1 Beecher’s second course features a pudding (hot, with a sauce, as was traditional), at least two unspecified pastry dishes (particular favorites were mince and apple pies), and one or more delicate sweet dishes selected from the family denominated custards and creams (which, confusingly, also included gelatin jellies). Her dessert focuses on fruit in various forms—fresh, preserved in syrup, candied, and dried—augmented by nuts, candies, and little cakes (such as macaroons and kisses).

When a dinner was served à la française, all of the items of each course were arranged on the table in a clever symmetrical pattern of top, bottom, middle, side, and corner dishes. There was nothing on the table other than the food, which, in effect, supplied the table decoration.2 Seated at opposite ends of the table, the hostess and host served the soup and the fish of the first course and the pudding and pastry of the second, while their guests served one another whatever dishes were nearest to them, helped by waiters who were standing by. Some guests not only had to serve but also slice or carve, for at French-style dinners roasts, birds, meat roulades, savory pies, and all else came to the table whole and intact. Fortunately, beasts requiring complicated dismemberment (like a roasted turkey) were typically set before the host, who was presumed to know how to dispatch them.

Catharine Beecher’s First Course (after the soup and fish had been served and cleared). Beecher’s serving pieces are much simpler than Raffald’s, as is Beecher’s dinner.

Place setting for 12-course dinner a la russe

By the 1860s, the rich and fashionable had abandoned service à la française in favor of service à la russe, or Russian service, and magazine writers, cookbook authors, and “behavior” experts were strenuously promoting this new serving style to middle-class women. While a French-style dinner was essentially a three-course buffet, a dinner à la russe was served in eight to fourteen separate small courses. In antebellum America, the more or less obligatory courses comprised, in the following order: raw oysters on the half-shell, soup, fish, croquettes or a creamed food in puff pastry, a roast with potatoes and a vegetable, game with salad (or salad only), a cold dessert, a frozen dessert with fancy cakes, and, finally, coffee. If a grander effect was wanted, other items could be grafted onto this basic template: an entrée (meaning a light meat or fish dish), and/or a vegetable, and/or a palate-cleansing sorbet could follow the roast; cheese and crackers could be served either following the game/salad or just before coffee; a hot dessert or a large cake could precede the cold dessert; and fresh, preserved, and dried fruit might follow the frozen dessert.3 It all sounds like quite a production, but in Practical Cooking and Dinner-Giving (1876), Mary Henderson opines that “it is very simple to prepare a dinner served à la Russe”—indeed, “after a very little practice it becomes a mere amusement.” Henderson’s nonchalance is less surprising than it seems. She presumes that many items will be purchased ready-made, either from a caterer or in cans, and that all of the cooking required will be done by servants, which any hostess who hazarded such a dinner would have had at the time.

Mary Henderson (1842-1931) was certainly one of the “rich and fashionable.” Shown here is her Washington DC home (built c. 1889) shortly before it was razed in 1949.

In addition to being served in many courses, Russian service differed from French in the way the food was presented. Each dish was sliced, sauced, and artfully arranged on a platter in the kitchen. A waiter then bore the platter to the table and offered it to guests one at a time, who helped themselves to as much as they wanted. There was never any food on the table except what was on the diners’ plates. But this does not mean that a table styled à la russe was unadorned. As Mary Henderson explains, “In serving a dinner à la Russe, the table is decorated by placing the dessert in a tasteful manner around a centre-piece of flowers.” By dessert she means “fruits, fresh or candied, preserved ginger or preserves of any kind, fancy cakes, candies, nuts, raisins, etc.”

Centerpiece with Flowers and Fruit

Most cookbooks published after the Civil War—including Fannie Farmer’s hugely influential Boston Cooking-School Cook Book, first published in 1896—take it as a given that formal dinners staged in upper-middle-class homes were served à la russe. But given the complications of Russian service (notwithstanding Mrs. Henderson’s airy assertions) and its profound departure from tradition, one suspects that many women merged the two systems—as Mrs. Flint did, to charming effect.

The savory dishes of Mrs. Flint’s November 1862 dinner were served in the Russian style, but not consistently in accordance with correct Russian procedure. The first of the savory courses was the popular turtle soup (three quarts total, ordered from a purveyor). Mrs. Flint’s houseboy, Edwin, ladled the soup from a tureen that had been set on a small table before a window. Henry Smith, a caterer and party planner hired for the occasion, passed the filled soup plates to guests. The soup was served with sherry, as most soups were at the time. Champagne was drunk with the remaining savory courses, as was typical in the day even when red meats were on offer.

The next course was creamed oysters in puff pastry shells, or “oyster patties,” a clever choice, as the patties could stand in either for the second Russian course, which was fish, or the third, which was typically a sauced morsel in pastry. Mrs. Flint notes that there were eight patties altogether, arranged “four on a dish, each patty cut across.” The waiters must have struggled to serve the patties, as each held a generous pint of filling (four quarts of oysters having been ordered for the dinner), which must have threatened to spill out.

Oyster Patties (courtesy of finecooking.com)

The third course may have been meant as the Russian roast course (which was the de facto Russian “main course”), but it was hardly a proper one. For one thing, the roast—a turkey “of nine or ten pounds”—was served in tandem with four boiled chickens, which had no place in this slot of a Russian menu. For another, the turkey was carved at the table by Mr. Flint, a violation of Russian protocol. As Mrs. Henderson explains, at a Russian dinner “the dishes are brought to the table already carved neatly for serving, thus depriving . . . the host of [displaying] his skill in carving.” However, hewing to the Russian style, both birds came to the table garnished with parsley, a new fashion that Mrs. Flint thought it worth her time to note.

While Mr. Flint was working at the turkey, Henry whisked Mrs. Flint’s chickens away and carved them in some unspecified place. Once carved, the birds were transferred to platters with their vegetable accompaniments, the turkey with deep-fried breaded mashed-potato balls, sweet potatoes, and squash; the chickens with boiled potatoes, sweet potatoes, and Matinas (a type of tomato, which may have been canned, considering the lateness of the season). The platters were then offered by waiters to the guests. At her sit-down suppers, too, Mrs. Flint was wont to offer two varieties of poultry, one roasted and one boiled, apparently with the expectation that guests would choose one bird or the other, not both. My guess is that she assumed her dinner guests would do likewise. Why Mrs. Flint thought it a good idea to serve two similar poultry dishes simultaneously is a mystery. Catharine Beecher paired her turkey with a ham, which seems a better choice.

The savory courses of the meal concluded with a three black ducks and “celery dressed,” that is, some sort of celery salad. This was a classic Russian game course—if not, one thinks, really the right game course for this particular meal, considering the bounty of feathered edibles already proffered. And contravening Russian convention once again, Mr. Flint carved the ducks.

Elizabeth Tuckerman Salisbury (1768-1851), by Gilbert Stuart, circa 1810 (courtesy of Worcester Art Museum)

The dinner now departed from Russian procedure entirely, in favor of a French-style second course constructed in the American way—that is, all sweet.4 Americans of the day sometimes called this course “dessert” (which was a bit confusing when a dessert of fruit followed) and sometimes “pastry and pudding,” after its principal constituents. At Mrs. Flint’s dinner, the pastry was apple pies, and the pudding was a hot plum pudding. By today’s definitions, the pudding was essentially a baked bread pudding with lots of raisins (the “plums”), not the classic, fancier plum pudding, which was boiled or steamed (now generally known as Christmas pudding in Great Britain and Ireland). Mrs. Flint had two recipes for the pudding in her notebook, one belonging to “Madam Salisbury,” who was likely the mother of Stephen Salisbury II, a frequent guest of the Flints, and the other copied from Amelia Simmons’s American Cookery, the first cookbook published by an American author, in 1796. Mrs. Flint observes that the pudding “was removed from the dish in which it was baked and placed on a small oval platter, which I liked.” This fashion had been abroad for some decades by 1862, but it seems to have been seldom done, so it is possible that Mrs. Flint had never seen it.5

Mr. Flint served the pies and Mrs. Flint served the pudding (which was surely accompanied by a sauce, although Mrs. Flint does not mention one in her notes). Since the pudding was hot, those guests who wanted both pudding and pie started with the pudding. Most guests, though, probably had room for only one or the other. Calves’ foot jelly, a spiced wine gelatin made with calves’ foot stock, “was passed around after the pudding and pies had been served,” says Mrs. Flint. The jelly was likely eaten off fresh plates supplied by the waiters.6

Finally, there was the dessert. In Miss Leslie’s Behaviour Book (1864 edition), American author Eliza Leslie recounts, in awed tones, a stultifying-sounding dinner à la russe staged for twenty-four in a grand English manor—waited by a butler and eight liveried footmen. The dessert that capped this extravagant dinner was essentially a Russian frozen dessert course yoked to a fruit course by dint of elaborate table setting. Mrs. Flint’s dessert was similar. First, the table was “entirely cleared, all the glasses removed,” Mrs. Flint writes. Then new place settings were brought on, consisting of “white china plates, each containing [a] white tea napkin,” with a “silver knife, fork, and spoon & fresh wine glass placed before every guest.” That word “containing” points to the surprising purpose of the tea napkins, which was to muffle unpleasant scraping noises when plates of ice cream were laid on top of the white plates, as was soon to occur. Leslie explains: “Next a dessert plate was given to each guest, and on it a ground-glass plate [for an ice], about the size of a saucer. Between these plates was a crochet-worked white doyly . . . . These doylies were laid under the ground-glass plate[s], to deaden the noise of their collision.”

Henry set ice cream next to Mrs. Flint but he was the one who served it—“on red china plates” (perhaps rented, as Mrs. Flint’s party tableware sometimes

Finger bowl

was), which were “placed on the white china, just as one places a soup plate on a dinner plate,” Mrs. Flint observes. After the ice cream had been eaten, the red plates were removed along with the tea napkins, and finger bowls were brought in and fruit was “distributed,” to be eaten off the white china plates. “The servants left the room,” Mrs. Flint writes, giving her guests an interval of privacy. As stylish as it was, this course, too, flouted proper Russian procedure, which decreed that the frozen dessert was to be served with fancy cakes. Mrs. Flint’s dinner did include cakes—squares of frosted pound cake, macaroons, and coconut cakes, all left over “from Wednesday,” when she had staged an evening party. But, following French custom, “coffee tea & cake [were] passed in the drawing room soon after we left the table,” Mrs. Flint writes.

Mrs. Flint’s notes tell us that this hybrid Russian-French dinner got off to a rough start. “Had I expected to have my dinner served in the way it was I should have had choice fruit & a few flowers, but I intended when I began my arrangements to have only my own people to serve it,” Mrs. Flint writes in her notebook. “Only fruit jelly & cranberry on the table when we sat down,” she continues. Clearly this was not the way the table was meant to look. What had happened?

For some reason that Mrs. Flint does not state, Henry Smith, assisted by his helper (described by Mrs. Flint as “a colored man”) and Edwin, ended up serving the dinner instead of Mrs. Flint’s “own people,” and Henry apparently pushed the dinner farther in a Russian direction than Mrs. Flint’s people would have. I don’t know if Mrs. Flint’s people would have brought out the savory foods in a single French-style first course, although this seems plausible, as Catharine Beecher composes her first course of virtually the same savory dishes that Mrs. Flint serves. But I do think that Mrs. Flint’s people would have simply set the savory dishes on the table and let the diners help themselves, for this is how things were done at Mrs. Flint’s sit-down suppers. If this was indeed the usual procedure at her dinners, Mrs. Flint ordinarily saw, when she sat down, a soup tureen and soup plates, all ready for her to serve, at her end of the table. And in the center of the table she was probably used to seeing a set of cut-glass cruets, or “casters,” containing pungent catsups and store sauces, for she reminds herself in her notebook always to set casters on her supper table.

Casters

But at a Russian-style dinner there was never soup on the table, for the soup was served by the waiters, nor were there casters, for all dishes came to the table already sauced. A Russian-style table was supposed to be decorated with a centerpiece consisting of flowers and fruit, but it seems that Mrs. Flint only decided to serve the dinner à la russe at the last minute, and did not have a chance to order the “choice fruit” and “few flowers” that the centerpiece required. And so Henry had put only the two jellies on the table, hardly a welcoming sight for Mrs. Flint’s dinner guests as they sat down. Mrs. Flint seems to have been a little embarrassed by this incident but not discombobulated. She simply wrote down what had happened so that she could avoid having it happen again.

[NOTES]

- In the eighteenth century the entire course was on the table when diners sat down. The soup and the fish were eaten first and then replaced (or “removed”) by new top and bottom dishes. The obvious drawback to this plan was that the bulk of the first course was cold and sodden with condensation under its covers by the time diners got to it. ↩

- This was the case in middling households. However, in very elite households, the center of the table was elaborately decorated, at least on company occasions, with flowers, fruit, sugar sculpture, porcelain objects, candles, and still other things. These items might be arranged on a long footed silver tray called a plateau. Or they might be displayed in a silver epergne, a large bowl elevated on a tall stem and surrounded by smaller bowls supported by radiating branches. ↩

- A serious disadvantage of a fourteen-course dinner à la russe was its length. Mrs. Henderson rails against “fashionable dinners” à la russe that stretch three or four hours; she feels that “every minute over two hours” is unendurable. (Today’s plotters of “tasting menus” might take note!) ↩

- By the late eighteenth century, the American version of French service entailed an entirely sweet second course, while the British second course contained a mix of savory and sweet dishes, as was traditional. Some diners chose savory dishes only, others only sweet, and others sampled both (changing their plates, of course). In Domestic Manners of the Americans (1832), Frances Trollope, an Englishwoman who visited this country in the early 1830s, expresses surprise at the American way, which she disliked, as she did virtually everything about this country. ↩

- Baked plum pudding will be the subject of a forthcoming blog post, and adapted recipes for Madam Salisbury’s and Simmons’s puddings will be provided. ↩

- Although service à la russe was supposedly dreamt up in Russia, the fashion was identified with the French, and in Britain and America most of the dishes served at Russian-style dinners were either French or Frenchified. This was particularly true of the desserts, which meant that pastry and pudding were rarely served. A plum pudding might be permitted for a holiday dinner (likely renamed in French, as le pouding, on the menu), but as lowly and contemptible thing as apple pie absolutely never made an appearance. The extraordinarily popular calves’ foot jelly was acceptable for the Russian cold dessert course, but a brightly colored, fruit-flavored French jelly was preferable. ↩